Max Wellborn left the Bank, at the beginning of 1928, to his hand-picked successor, Eugene R. Black, whose daughter was married to Wellborn's son. Black was a convivial attorney who had practiced law for 28 years before he became president, in 1921, of the Atlanta Trust Company. Nearly three years before Wellborn's retirement, according to his biographer, Wellborn told Black, "I'd like to have you succeed me," and Black replied, "That would be bully. How do we go about it?" Three major Atlanta banks, by tradition, nominated one of the Class A directors, and in 1925 Black was nominated and elected without opposition.

A high-spirited leader

Black probably could have won election without help from Wellborn because Black was one of the best-liked men in the city. Veteran employees of the Bank who were low-ranking clerks in 1928 remember Black fondly because he remembered them, learned their names, would give them a pat on the shoulder and an encouraging word when he strolled through the Bank. He was high-spirited and stayed up most of one night on a business trip to shoot craps in the Pullman car with a few younger officers of the Bank. He was a practical joker and was known as one of the funniest and most engaging public speakers in the city, perhaps second only to his father-in-law, celebrated Atlanta Constitution editor Henry Grady, when it came to oratory. According to one story, he was crossing south Georgia once in his chauffeur-driven Bank car when they were stopped in a small town for speeding. When he learned that the fine was $5.00, Black gave the policeman $10.00 because he would be returning through that town in a couple of hours.

Wellborn was militant, austere, and courageous; Black was genial, generous, and resourceful. Wellborn may have ridden off into retirement as the hero of the Battle of 1920, but that victory would soon become a skirmish in comparison to the war Black would have to wage against the greatest depression of them all, one that just kept coming and which devastated the region, as it did the nation. That depression brought Franklin Delano Roosevelt to the White House, and Roosevelt brought Black, an old acquaintance, to Washington, the only officer of the Atlanta Fed in the Bank's first 75 years to become the head of the Federal Reserve System. In 1933, shortly after every bank in the nation had been closed temporarily, it became Black's job to lead the System through what was certainly its darkest hour.

But first he had to steer the Atlanta Fed through severely troubled waters. His administration began routinely, with a bank relations campaign to "cultivate good will and cooperation." To this end, officers visited 160 banks in the first half of 1928, and Black wrote to the president of each member bank. He was pleased to discover "that the member banks have a warm regard for our bank."

The country changes its currency

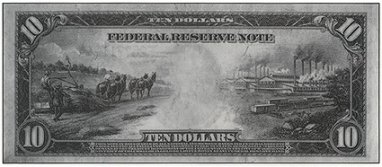

If it seemed as if the dollar were shrinking in those inflationary days as the 1920s sped toward their roaring climax, it was no illusion. On July 10, 1929, the U.S. Treasury Department introduced its new, smaller U.S. currency. Larger, old-style currency was to be retired gradually as bills became unfit, so new currency was supplied to Reserve Banks in proportion to the amounts of unfit currency they normally retired. Reserve Banks portioned it out to member banks by the same rationale. Nonmembers could get new currency from a Fed Bank by exchanging old currency for it—and paying the freight both ways.

The new currency (the size and design still used today) was printed on a newly developed paper stock with high folding endurance. Like the old currency, the new contained silk fibers, but where the old currency had those fibers arranged in rows, the new scattered them randomly. The new currency would be harder to counterfeit, the Treasury Department explained. Within two days the Atlanta Fed had placed more than $13 million of the new bills in circulation.

Internally, even though fiscal agency work had dried up and check clearings continued to be low, the Bank was humming along with plenty of work to do, most of it in the credit area. "From the mid-twenties until the bank holiday in 1933, the Discount function was very active, up to 40 clerks working in the discount and credit functions," officer V.K. Bowman later recalled. "The daily rush to inspect the notes received for negotiability and correctness, the pulling of the credit information on all notes, the necessary review and notation on the applications, preparation of discount status of the respective bank requesting further credit, all completed in time to present it physically to the 2 P.M. meeting of the Discount Committee, made old people out of young people rapidly."

|

|

| An example of the 1929 currency redesign. |

While the Board in Washington was not particularly critical of the credit policies of the Atlanta Bank after 1922, its examiners were rigorous, Bowman recalled. "The periodic examination by the examiners of the Federal Reserve Board was a nightmare in those days. All notes had to be balanced by the 10 classes or divisions then required. . . . A detailed listing of notes held for each bank, showing those forwarded to the bank in anticipation of maturity, was prepared as a reconcilement. Nearly every typist and steno in the bank was used. Financial statements on all notes of over a designated amount had to be pulled for review by the examiners. Then the big argument started, tying to justify the rediscounting of certain notes. Examination after examination—Creed Taylor, Deputy Governor; Ward Albertson, Assistant Federal Reserve Agent; and the writer argued practically the night through with the Chief Examiner over the lines, amounts advanced to banks, and the condition of the member bank in requiring such advance."

The Sixth District economy was building up steam in 1928. Credit demand was strong, and rediscounts surged to $1.3 million that year, easily the most credit activity the Bank had seen since 1921. Interest rates moved up rapidly between February and July, as the discount rate was raised from 3.5 percent to 5 percent, and rates on commercial loans went as high as 6 percent. Rediscounts continued to rise in 1929.

Reining in stock speculation

Concern spread in 1929 about bank lending to stock speculators. A rush among investors to capitalize on rising stock prices was driving up interest rates and making it difficult to stop credit from flowing to Wall Street. The Board in Washington wanted member banks to restrict their lending to local businesses and not "export" money to New York, especially if they were rediscounting with the Fed. Even early in the year, the Fed wanted to avoid financing the stock speculation of 1929.

Chairman Oscar Newton, the Mississippi banker who had succeeded Joseph McCord in 1925, noted that Sixth District member bank loans to New York brokers and dealers dropped from $28 million to $22.5 million between October and December 1928. The Atlanta Bank evidently succeeded in persuading member banks to stop such lending because Black was able to report in August 1929 that only two member banks that were borrowing from the Fed were lending on call in New York, and then only a total of $334,000.

Jitters in Florida

As early as May of that year, Black was urging caution in extending credit to member banks and sounding rather unlike Wellborn: "We are giving close study to credit conditions in our territory and are endeavoring to protect the bank in all lendings to member banks. . . . In the case of any bank in a weakened or extended condition, we are protecting our bank by the requirement of additional collateral. In the case of some banks we are declining any rediscounts because of the impaired capital of such banks. . . ."

Florida remained particularly touchy. The failure in July of a bank in Tampa set off bank runs in Gainesville and St. Augustine and led the banks in St. Petersburg and Orlando to invoke their right to require 60-day notice for withdrawals from savings accounts. Black and his deputy rushed to the Tampa area with $6 million in cash to turn back runs on two member banks there in October.

Such activity would become all too common before the Depression hit bottom, but in 1929 it was novel and experimental. About the efforts to slow savings withdrawals, Black noted, "We are watching this drastic measure with these banks in an effort to learn whether such a step can be successful with a commercial bank." There certainly was concern about what Black called "general unrest among the depositors in a large number of Florida banks," but there was no reason to see the problem as anything other than local and temporary. After all, the trouble in Florida stemmed from the appearance that spring of the Mediterranean fruit fly. To fight the fruit fly, the Florida Citrus Exchange had slapped an embargo on fruit and vegetable shipments, which left many growers unable to repay loans.

But on October 29 the stock market crashed and a national economic collapse had begun. The market crash certainly was disruptive within the banking system, but few bankers in 1929 saw it as deeply destructive. In spite of the Federal Reserve System, money still moved through the correspondent banking network from local communities to the New York banks, where it was used to finance stock buying on margin. After Black Tuesday massive loan calls threw this process into reverse. The New York Fed eased the credit demands there with stepped-up rediscounting and purchases of government securities. The New York commercial banks took up some of the slack by expanding their loan portfolios. The Atlanta Fed recorded moderate increases of $5 million in government securities and $5.4 million in loans to members.

It seemed at that time that the banking system, aided by the Fed, had met the crisis. Black considered it to be "a matter of congratulation that the Stock Exchange situation which existed in New York did not result in a business panic or disaster and that it was not accompanied by the collapse either of brokerage houses or financial institutions." He did, however, anticipate some aftershocks.

The aftershocks were profound but not sudden, and the worst of the banking system collapse did not come until 1932-33. There was one notable Sixth District bank failure before the end of 1929, however. The Atlanta Trust Company, the bank Black left two years earlier to become governor of the Federal Reserve Bank, averted technical bankruptcy in December when it was taken over by Citizens and Southern National Bank.

| Previous | Next |