The central bank the United States has today might have been entirely different. The rapid, unstable growth of the U.S. economy after a century and a quarter was compelling the nation to choose a central bank, but what form of bank was hotly contested. There was nothing inevitable about the formation of the Sixth Federal Reserve District or the choice of Atlanta as a regional bank site. That took some doing.

Depositors attempt to claim their funds during the 1907 Bank Panic.

The Panic of 1893 set off the worst depression the United States had yet seen. It caused not only bank runs (400 bank failures in six months) but even a run on the U.S. Treasury gold fund, which fell from $190 million in 1890 to $41 million by 1895. A badly shaken President Grover Cleveland played his last card and sent an emissary to New York banker J.P. Morgan. A Morgan-led syndicate threw a $65 million bond issue behind the U.S. gold standard and prevented collapse—at a considerable profit to the banks. The move was politically unpopular, but when the country had to have a central banker, there was nowhere else to turn.

Central banking was always a thorny issue in America. Alexander Hamilton's First Bank of the United States, created in 1791, expired when Congress refused to renew its charter in 1811. The Second Bank of the United States, barely rechartered in 1816, was scuttled by the impressive reelection of Andrew Jackson, a central bank foe, and the Bank's charter was not renewed in 1836. A central bank meant too great a concentration of economic power for many in the young republic to accept.

Suspicions of concentrated economic power remained in 1907, but the economy clearly had outgrown its banking system. A panic that year, while brief and largely confined to Wall Street firms, underlined the dangers of an inelastic currency and an illiquid banking system: the money supply could not expand or contract in response to economic conditions, and too often banking assets flowed to New York in good times and returned slowly and uncertainly to local banks and depositors in bad times. In 1908 Congress passed the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, which provided for emergency currency issues and created the National Monetary Commission to investigate and recommend a long-term solution.

That commission, headed by Republican Senator Nelson Aldrich, studied the central banks of Europe and in 1911 recommended a similar arrangement for the United States: one central institution empowered to issue currency and rediscount commercial paper, governed by a board of commercial bankers. It might have been the blueprint for the Federal Reserve System, but the election of 1910 gave Democrats control of Congress for the first time in nearly 20 years. Populist William Jennings Bryan assailed the Aldrich plan as a tool of the hated New York "money trust" and proposed a decentralized system controlled by the government. The election of 1912 put Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, in the White House.

The plan that moved through Congress in 1913 was fashioned largely by Virginia Representative Carter Glass. It called for 20 or more privately controlled regional banks that would hold reserves and issue currency. Wilson asked for one change that would have far-reaching ramifications: he wanted a "capstone," a publicly appointed Federal Reserve Board to provide uniform guidelines for the regional banks. The bill was treated roughly by Congress and barely survived a couple of challenges, but the Federal Reserve Act was passed by the House (287-85) and the Senate (54-34) and signed into law by an elated President Wilson on December 23, 1913.

On the occasion, Agriculture Secretary David Houston wrote in his diary, "The impossible has happened. Today, Tuesday, December 23d, the currency measure became a law. . . . It was passed by a Congress dominated by the Democrats, two-thirds of whom had been unsound on currency questions and a majority of whom can scarcely be said to have understood what the measure meant and would accomplish. The majority of the Republicans had also had an unenviable record on the currency." Most of the commercial banks that eventually would become members of the Federal Reserve System remained overtly hostile to the legislation throughout 1913.

By the time the bill was passed, the number of regional banks had been scaled back to at least eight but no more than twelve; the Federal Reserve Board had been set at seven members, including the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency; and a Reserve Bank Organization Committee was designated to draw up the Reserve Districts and choose the Bank sites.

Once the bill became law, bankers who had denounced it began to campaign for a Federal Reserve Bank in their city. A cross-country tour by the Organization Committee unleashed a frenzy of boosterism as most major cities clamored to get a Reserve Bank. Secretary Houston, a member of the committee, complained, "I think the Census experts are mistaken as to the number of cities in America. Certainly nobody could have imagined that so many had strategic locations."

Atlanta rallies its forces

Getting a Federal Reserve Bank was particularly important for the deep South. No region had suffered more from the concentration of financial capital in the Northeast. The Civil War had devastated the southern economy, and Reconstruction policies kept the South poor when industrial centers were surging forward in the North and Midwest. The banking system had been slow to develop in the South. Few southern communities could raise the $50,000 minimum capital required for a national bank prior to 1900. State-chartered banks were small and poorly regulated. Most loans came from merchants who sold provisions to farmers on credit. Loan rates at banks were high, and bank failures were frequent.

The general prosperity of the 1880s had buoyed the South somewhat. A growing number of textile mills provided a stronger market for cotton, still the region's cash crop. Higher commodity prices raised the standard of living, but not to the level of the rest of the nation. Cotton was king in 1914, and southern politicians like "Cotton Ed" Smith of South Carolina and "Cotton Tom" Heflin of Alabama, both U.S. senators, prized their nicknames. Banks in the South grew from 1,007 in 1881 to 9,207 by 1914. Most of them, however, were state banks, which in the South were notorious for being undercapitalized and poorly managed.

The acknowledged financial center of the South was New Orleans, with a population of 361,000 in 1914 and banking deposits of $75.2 million in 1913.

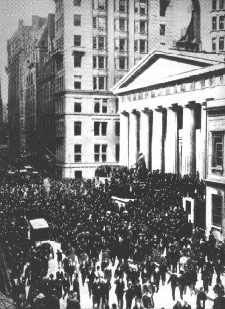

Proponents of Atlanta as the site of a Federal Reserve Bank prepared this map to illustrate the city's central location at the heart of the South's important cotton industry. |

Atlanta, a surging rail center, had a population of 179,000 and banking deposits of $35.9 million. The old seaports—Savannah and Charleston—still were important trade centers, and Birmingham was making its mark as a steel town. Florida was a mass of undeveloped land. Jacksonville, its largest city, had only 70,000 residents.

Atlanta's bankers and business leaders were determined to win a Federal Reserve Bank for their city. It was a transportation hub, already something of a banking center (notably high, for its size, in check clearings) and the preferred regional office site among many of the nation's manufacturers and merchandisers. Nor did it hurt that Treasury Secretary William McAdoo had been born and raised in Georgia or that President Wilson had launched his law career in Atlanta.

The chamber of commerce and the local banks built a strong case to present to the Organization Committee when it came to Atlanta on February 13, 1914. The Atlanta team pushed the city as the financial capital of a region that would include Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Tennessee, shrewdly excluding from the hypothetical district New Orleans and Richmond, its most formidable rivals. The Georgian, a Hearst newspaper, editorialized for Atlanta, noting, "The cities which possess the regional banks will become the financial centers of their entire sections. It is history that when a city holds the purse strings, soon it dominates in all other lines. One of the things which has built New York is the fact that New York always has held all the money—and one of the principal objects of the currency bill is to take some of this power away from New York."

After the presentation in Atlanta, Georgia Senator Hoke Smith continued the campaign in Washington, assisted by local bankers and business leaders, who made frequent visits.

The Organization Committee faced a number of important decisions in drawing District lines and choosing regional bank sites. Democrats favored broad regional distribution; yet banking resources were clustered in lower Manhattan. It was impossible to carve the real estate into roughly equivalent tracts and simultaneously carve the banking resources into roughly equal amounts.

Some plans called for dividing Manhattan itself between two Districts. Another plan would have placed all of the Reserve Banks north of the Ohio and Potomac rivers. The Federal Reserve Act set $4 million as the minimum capital subscription for a Reserve Bank, and so thin were the financial resources of national banks in the South and West that considerable gerrymandering was necessary in some regions to make the capital standard attainable. Since Reserve Bank officers would travel to Washington sometimes, preference was given to locations closest to Washington.

The pie is sliced

When the Reserve Bank sites were announced, there was rejoicing in Atlanta, as well as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Richmond, Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Dallas, and San Francisco. Crowed W.J. Blalock, president of Fulton National Bank, "This bank will enable us of the southeast to finance our own needs. . . . It is the biggest thing for this section that has happened in a long time."

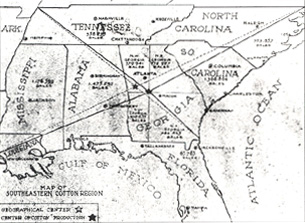

There were angry protests in cities that were passed over; especially disgruntled were New Orleans and Baltimore. Citizens of New Orleans staged a mass protest on April 5, and a cartoon in the Daily Picayune showed Justice knocking without effect on the door of the Federal Reserve Board. Controversy spilled over onto the floor of the House, where Representative Glass had to defend the Committee against charges of political favoritism.

A cartoon reflects New Orleans' disappointment in being passed over for a Federal Reserve Bank head office. |

The Organization Committee chose the cities first, then drew District lines around them. The Sixth District was drawn to include Georgia, Florida, Alabama, central and eastern Tennessee, southern Mississippi, and southern Louisiana, including New Orleans. Some banks petitioned to be included in different Districts, and adjustments were made, mostly before 1920. Few changes were made to the Sixth District. Two banks in central Tennessee had to be persuaded not to seek a transfer to the St. Louis District, and a few central Louisiana banks, once a branch had been established at New Orleans, were shifted, at their request, into the Sixth District.

Once the Federal Reserve Bank sites had been chosen and the Districts defined and largely accepted, attention shifted to selecting a Federal Reserve Board, President Wilson's unifying "capstone." Treasury Secretary McAdoo and Comptroller of the Currency James Skelton automatically were members. In making his other five appointments, Wilson tried to mollify the bankers, who had fought the provision for a politically appointed Board. Two of the nominees, while acceptable to bankers, drew such strong opposition from Wilson's Progressive allies that their nominations had to be withdrawn. Ultimately confirmed were Wall Street financier Paul Warburg, economics professor Adolph Miller, Boston attorney Charles Hamlin, railroad executive Frederic Delano, and Birmingham banker W.P.G. Harding. The Organization Committee dissolved, and on August 10, 1914, with Hamlin serving as governor (the counterpart to today's chairman), the Federal Reserve Board took over the task of organizing and chartering the Reserve Banks.

One of the Wilson nominees who escaped public attention in the confirmation process was Harding, who would serve as governor of the Federal Reserve Board from 1916 to 1922 and play an important role in the affairs of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. W.P.G. Harding was something of a prodigy—a University of Alabama graduate at age 16 and president of the state's dominant bank (First National of Birmingham) by age 38. He was as surprised as anyone by his nomination. A reserved, studious, hard-working man, Harding, to promote Birmingham as a Reserve Bank city, had boarded a train in Montgomery on which Wilson confidant Colonel Edward House was traveling and rode with House as far as Opelika, pointing out the economic advantages of his city. The Alabama banker heard nothing more until newspaper reporters told him he had been nominated for the Federal Reserve Board.

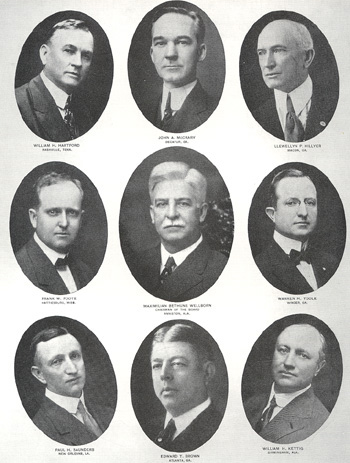

The first Board of Directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. |

A bank is assembled

Organization of the District Banks was proceeding in the summer of 1913. They were to be quasi-private bankers' banks, owned by the member banks, which would buy all the stock of the Reserve Banks and receive dividends for it. In one sense, the District Banks would operate to maximize their earnings, which were originally foreseen to derive primarily from purchasing loans at a discount from member banks. However, their fundamental public policy mission required that, after dividends and operating expenses were covered, additional earnings were to be remitted to the Treasury. District Reserve Banks would answer both to the Federal Reserve Board in Washington and to a local board of directors. The two boards had different but overlapping authority. The Washington Board could and did exercise some control over activities of the District Federal Reserve Banks, but, in general, the Banks were more autonomous before 1935 than they are today. The original Federal Reserve Board's powers had been carefully limited and were often resisted.

To organize, the Atlanta Bank needed nine directors; three of them (Class C) were appointed by the Board in Washington, and six were elected by the member banks—three bankers (Class A) and three business leaders (Class B). The chairman and vice chairman would be chosen from the Class C directors. Then the Bank would need a governor to direct a small staff of knowledgeable bankers and clerks, notably a cashier, an auditor, a bookkeeper, a credit manager, and a discount clerk, as well as some currency handlers who were quick counters and able to spot counterfeits.

The Class A and B directors elected in the summer of 1914 included bankers Llewellyn P. Hillyer of Macon, Francis W. Foote of Hattiesburg, and Warren H. Toole of Winder, Georgia, and business leaders Dr. P.H. Saunders, a New Orleans mortgage securities dealer (and former Greek professor); W.H. Hartford, a Nashville industrialist; and J.A. McCrary, a Decatur, Georgia, construction contractor. The three Class C directors were Maximilian B. Wellborn, Anniston, Alabama, banker, as chairman; William H. Kettig, Birmingham industrialist; and Edward T. Brown, Atlanta attorney. Brown, related by marriage to President Wilson and present at the signing of the Federal Reserve Act, was an early leader, and McCray was an enduring activist until his death in 1953. But the individual who would dominate the Bank for the next 13 years was Max Wellborn.

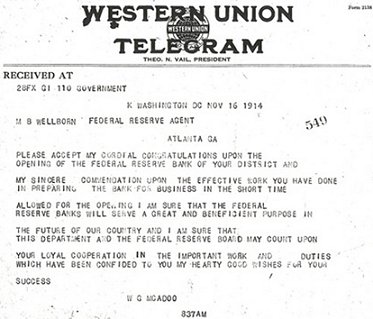

A telegram from Treasury Secretary McAdoo heralds the opening of the Atlanta Fed. |

Wellborn was a self-confident entrepreneur who had started five banks in Anniston. Among his admirers was W.P.G. Harding. When Harding accepted a position on the Federal Reserve Board, he tried to recruit Wellborn to replace him as president of the First National Bank of Birmingham at a salary of $18,000. Wellborn declined. Harding tried again in August 1914, this time to persuade Wellborn to become chairman and Federal Reserve agent of the new Reserve Bank being organized in Atlanta. Although the salary for that position was only $9,000, Wellborn accepted. The position of chairman later became a post held by an outside director, but Wellborn was a full-time executive of the Bank and, under whatever title, its most forceful leader until his retirement in 1927.

The post of governor (retitled president after 1935) went to Joseph A. McCord, an Atlanta banker who had served from 1907 to 1914 on the currency reform task force of the American Bankers Association, which worked with Congress on the Federal Reserve Act. McCord was part of the group that lobbied to bring a Federal Reserve Bank to Atlanta, and he made one of the speeches to the Organization Committee when it came to Atlanta. He was approached by Harding, then hired at a salary of $9,000 at the first meeting of the Atlanta board on October 19, 1914. Brown's firm, Brown, Randolph, Parker and Scott, was retained as the Bank's counsel.

At the third board meeting, on October 30, just 16 days before the Bank opened, the Bank's first quarters were chosen, in the new Hurt Building. Rent was $6,500 for the first year, $8,000 for the second, and $9,000 for the third.

The board met again the following day to formally hire a staff of 13 for the Bank. It would include, in addition to the governor, a secretary-cashier, assistant secretary-treasurer, auditor, credit officer, discount clerk, general bookkeeper, ordinary bookkeeper, statement clerk, secretary to the chairman, stenographer, messenger, and porter. Some day the Bank would need a chief clerk, a general utility man, a mail clerk, and tellers, the board decided, but it chose to save money by having other officers perform those duties at first.

Bound for Atlanta

Most of the new employees came from commercial banks around the District, usually not from Atlanta. One young man from New Orleans, W.E. Miller, left a revealing account of coming to work for the Atlanta Fed in 1916.

"Several months later [J.B. Pike, the Atlanta Fed's first cashier] returned to New Orleans and visited the Hibernia Bank & Trust Company where Leo Volker, Warren Seebt and I were transit clerks. Mr. Pike asked us if we would like to go to Atlanta to work for the Federal Reserve Bank. I was making $35.00 a month and the other two boys were making $30.00 a month. Mr. Pike said he would double our salary. We told him that we would accept the position providing our parents consented to our going to Atlanta. I told Warren I didn't own a suit case. He told me that I could put my clothes in his trunk. We told the folks at the bank good-bye. . . .

"We left Saturday morning at 7 a.m. on June 29, 1916 by train. . . . The fare I think was $10.00 round trip. It was an old coal burner, no screens and velvet seats, the itchy kind. . . . We arrived in Atlanta at 1 a.m. Sunday. Mr. Gradberry, a teller working for the bank, met us at the station and brought us to the YMCA, a very nice place for young fellows to stay. . . .

"July 1st was the big day. On our way to work we reached the section known as five points. We didn't know what direction to take. Finally, we found the bank. . . . We first met Mr. Pike and he introduced us to Governor Joseph McCord, Mr. Wellborn, Chairman of the Board, Mr. Bell, the Assistant Cashier, and then took us around the bank to meet the other employees. We didn't have a large force. . . .

"Mr. McLarin, our Transit Manager at that time, suggested that we purchase a ledger and write with pen and ink the names of the banks in alphabetical order, and the amount of each letter to be posted opposite each name. This system was then adopted. Each page had sufficient columns for the week. If the cash letter [summary of checks sent for clearing] was not paid in full, we had difficulty in showing the exception due to lack of space. The unpaid cash letters and exceptions, if any, shown in the ledger would be the outstanding items and should agree with the General Books. . . .

"Atlanta had ‘Blue Laws'. . . . The only recreation on Sunday was going to Church, visiting the zoo, or taking a long walk. The governor did allow us to write letters at the bank on Sundays. At that time every officer and employee, except the Governor, was from out of town. Fortunately, the Georgia Laws allowed you two quarts of whiskey a month. We received ours by Express from New Orleans. . . . It was pretty blue for us coming from New Orleans which was a wide open town. I would get a little more home sick when the carnival season came around."

| Previous | Next |