In August 1914, as the new Federal Reserve Board members were being sworn in and member banks were electing directors, World War I broke out in Europe. The new central banking system of the United States would operate in a world far different from anything the creators of the Federal Reserve Act envisioned. Although the war profoundly affected the Reserve Banks, the first monetary consequence—a quick expansion of the currency—already had been accomplished by banks under the Aldrich-Vreeland emergency powers before the Reserve Banks were opened. The outbreak of war disrupted European markets, a blow to cotton producers in the Sixth District. It was a time, Wellborn reported a year later, when "the general business conditions of the district were undergoing a most demoralizing depression."

The Atlanta Fed opened with a business plan dictated by the region's chronic capital shortage and the unstable markets for its commodities.

Joseph A. McCord, Governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta from 1914 to 1919. |

The Bank would issue currency as needed and clear checks sent to it, but its chief purpose would be to provide credit by buying ("rediscounting") loans from member banks and paying them money with which they could make additional loans. The Atlanta Fed thus would help growers avoid having to dump their crops at a time when prices had plunged by allowing them to wait for higher prices. The Atlanta Bank also planned to use its rediscounting to make certain there was enough credit to meet the high demand of the planting season. Wellborn and Harding devoted considerable attention in 1914 and 1915 to the mechanics of rediscounting cotton paper, the definition of acceptable paper, and the collateral required. They intended to use the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta to strengthen the cotton economy of the South and free it from dependence on the New York banks.

"They're off and . . . creeping"

With such visions of economic revitalization, the leaders of the Bank probably were disappointed when few member banks showed up to borrow during the Reserve Bank's first months of operation. Indeed, the Reserve Banks generally found little demand for their services before 1917, and this was a source of both financial and political embarrassment. The Reserve Banks were expected to be self-supporting. Although the Reserve Banks were flush with gold and currency allocated by the Treasury Department or collected from member banks as reserves, their only income came from earning assets, and these were almost exclusively, at first, the loans members rediscounted with the Reserve Banks. The banks received no appropriation from the government for current expenses. The trickle of initial business meant that many of them were hard pressed to generate enough earnings to pay their bills. Issuing currency entailed some expense and provided no revenue.

The Reserve Banks opened at a time when demand for credit was low and was being met by traditional providers, primarily the major New York banks. Concerned that 49 member banks were ignoring the Atlanta Fed's rediscounting and continuing to borrow from correspondents, Wellborn polled them to find out why. With the exception of one bank (which argued that the Fed should accept paper of any character offered by a member bank), they all expressed "no dissatisfaction with the Federal Reserve Bank. Some state they prefer to borrow money in New York, as heretofore, believing it involves less trouble, while others say they can obtain a lower rate in New York than they can with us," Wellborn discovered.

The Atlanta Bank wished to set its discount rate initially at 5 percent, but the Board in Washington insisted on 6 percent. When nothing happened at this level, Senator Smith of South Carolina conveyed his disappointment to Wellborn, who wired the Board in Washington, urging cooperation: "Board of Directors . . . has fixed discount rate four and one-half for thirty days and five per cent other maturities. We request that you confirm same and advise by wire. Good banks this district offered money New York at less than five per cent and we have practically no demand for funds at present rates. . . . Imperative in our judgment that we be placed in position to do some business." The discount rate was lowered, and, when the borrowing season for cotton arrived in the fall of 1915, rediscount activity picked up.

First year in review

By the end of 1915, after 13 months of operation, Chairman Wellborn could claim in the Bank's first annual report that the Sixth District ranked second in the System in total note issue because "a great deal of currency is required for use in moving the cotton crop." By late 1915 he could say, "Our bank having to handle so large a number of rediscounts, the force is constantly at work, frequently into the night, during the autumn and winter seasons." By year's end 1915 the Bank had discounted 22,252 loans worth $35 million.

Much time was spent that first year exploring "the intent and meaning of the Federal Reserve Act and the class of paper eligible for rediscount,"

Bank staff at work in the original quarters at Atlanta's Hurt Building. |

Wellborn wrote in his report of 1915. Setting and communicating clear standards was troublesome, and many loans presented for rediscount were rejected for noncompliance. The Atlanta Bank was able to demonstrate early its value to cotton growers, who saw prices fall sharply when the war disrupted their European markets. Wellborn reported that through its rediscounting activity the Atlanta Bank aided substantially in "causing and maintaining the favorable prices of cotton." He also noted that "the quality of loans by member banks is much improved; bankers are requiring better paper—paper that will be liquidated at maturity—with a view to eligibility at the Federal Reserve Bank." The Bank reported a net operating profit for 1915 of $82,532.

The Federal Reserve Board in Washington thought that was not good enough. The District Banks as a whole were operating at a loss, and a majority of the Board was convinced that too many Reserve Banks had been formed and that those in Atlanta, Dallas, Kansas City, and Minneapolis should be eliminated, and possibly those in Richmond and Boston as well. If the U.S. Attorney General had not issued an opinion that only Congress could terminate Federal Reserve Banks, the Atlanta Fed might have had a short history.

The banks that would not join

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, like its peers in other Districts, started slowly because banks resisted joining the System. All national banks were required to be Federal Reserve members, and the fear that national banks would convert to state-chartered banks to avoid membership was groundless. But the hope that large numbers of state-chartered banks would elect to join also was unfounded. The majority of banks in the United States were state-chartered, and the effectiveness of the Federal Reserve System depended in part on whether it attracted enough state banks to give it a critical mass in the banking system. It is not surprising, therefore, that Reserve Banks made evangelical efforts to persuade state banks to join. Such efforts met with meager success, and membership remained a problem until 1980, when the Monetary Control Act removed the remaining disincentive to membership by requiring all depository institutions to maintain reserve balances with the Fed.

The membership problem was particularly daunting in the Sixth District, where there were fewer national banks than in other Districts, where state banks were smaller and disinclined to be regulated, and where anything federal was suspect. There was another problem. Checks cleared through the Fed were, from the very beginning, to be paid at face (par) value. Many small banks, particularly in the South and Midwest, were accustomed to withholding a small "exchange" fee, typically one-eighth of a percent of the check's value. They felt they were entitled to this fee, and they felt it strongly.

In the South it became a highly emotional issue that would not die. Because only banks that would pay at par could clear checks through the Federal Reserve, the Atlanta Fed found itself at odds with the contentious nonpar banks of its District. This problem endured until 1979, long after it had been laid to rest in other parts of the country. By then, the Louisiana legislature had compelled the last nonpar banks in the country, still kicking and screaming, to join the twentieth century payments system.

The original directors of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, knowing the strength of regional feeling on this issue, recommended that only member banks in cities of more than 30,000 be required to remit at par, but the Board in Washington refused to exempt country banks from the par clearing requirement. This policy was regarded as throwing down the gauntlet by many of the smaller state-chartered banks, who regarded as a mortal enemy the Federal Reserve Bank that hoped to enlist them as members. Progress initially was glacial: from one state member bank in 1914 to two in 1915, four in 1916, and eighteen in 1917.

It was hardly surprising, therefore, that the Bank's check-clearing services were little used at first. The 1915 annual report stated that 73 banks cleared an average 440 checks daily, 204 on Atlanta banks, 207 on District banks outside Atlanta, and 29 on banks in other Fed Districts. Wellborn concluded, "Our bank has earnestly endeavored to cooperate with the Federal Reserve Board in putting into effect the voluntary clearing system proposed by your Board, but the result has not been satisfactory." Most checks continued to be cleared through correspondents. Banks objected to using the Federal Reserve, Wellborn explained, because they did not want to give up exchange charges, because unpredictable debits made it difficult for them to maintain reserves at the proper level, because the only out-of-District points served were Federal Reserve Bank cities, and because the Fed would not clear checks drawn on nonmember banks.

Efforts to uncrown "King Cotton"

Low membership, minimal check clearing, and sporadic rediscounting business did not stop the Atlanta Fed from making vigorous efforts to combat the region's number one economic problem: its dependence on a single, volatile commodity. Wellborn, for one, was convinced that the South needed to provide flexible, stabilizing financial support for its leading crop at the same time it moved to diversify its economy. Toward this end, the Bank pursued aggressive credit policies which sometimes provoked murmurs from Washington, and it became an early and active issuer of currency for its thirsty District. There was seasonal demand for currency to pay growers for their cotton, and the Atlanta Bank issued $18.9 million of Federal Reserve notes by the end of 1915, making it the second most active money issuer in the System, the first in proportion to its capital.

The Austell House at 92 Marietta Street once stood on the site of the Atlanta Fed headquarters. |

When cotton production fell by five million bales the year after the cotton squeeze of 1914, Wellborn rejoiced. "Such conditions brought most forcefully to the mind of the Southern farmer the imperative need of crop diversification," he wrote in the 1915 annual report. "The ability of the Federal Reserve Bank and of the southern banking organizations to move the cotton crop," he said, had brought "the long anticipated relief from seasonal financial pressure." The District desperately needed "financial encouragement for new enterprises," he insisted.

He noted with satisfaction "the great progress in diversification of crops," which he said was limited only by "the great need of an adequate supply of capital to prepare for and finance the improvements necessary to profitably grow and market crops which have heretofore been grown to a limited extent only."

While his vision was essentially correct, he was inclined, in assessing 1915, to declare victory prematurely. It would be at least another 20 years before the South moved away from its dependency on cotton, but the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta had found a continuing mission in its efforts to improve the rural economy of its District.

It may surprise those familiar with the billions of dollars of "profit" that the Federal Reserve Banks return to the U.S. Treasury each year to learn that in its earliest years and again during the Depression, the Reserve Banks had to struggle to make ends meet. In its first full year of operation, the Atlanta Bank earned only $236,460, more than enough to cover its modest expenses of $153,460, but the remainder—$82,532—fell far short of the $145,320 it would have needed to pay the 6 percent dividend owed to shareholders. Like many a struggling business, it suspended its dividend that year. The problem was simply a dearth of earning assets. Income rose slightly in 1916 and expenses fell, leaving a net income of $129,307, from which a partial dividend of $70,941 was paid. Employees even received $10 Christmas bonuses in light of the prosperity.

The war ignites the Fed

The slow times of 1914-16 in the Atlanta Bank turned out to be the calm before the storm. World War I brought an economic roller-coaster ride. By 1917 the country and its fledgling central banking system were riding an economy spurred by an unprecedented explosion of government debt to finance war efforts, strong demand for industrial and agricultural goods, rising prices, and strict wartime controls and rationing. The war decisively ended the Reserve Banks' anemic earnings. The war-driven economic expansion increased demand for credit: earnings from rediscounts in Atlanta rose from $141,774 in 1916 to $1,758,000 in 1918, for example.

But what really transformed the Atlanta Fed and its counterparts in other Districts was the flood of government securities. Before the war, government securities were scarce, infrequently traded, and not generally available to Reserve Banks. During the war, the Fed was introduced to a role that would become familiar over the next 30 years—as the captive finance company of a U.S. Treasury with huge financing needs and a compelling desire for low rates. The national debt soared from only $1 billion before the war to $26.6 billion by August 1919. The Treasury began its war financing by selling bonds at such low rates only the Reserve Banks would buy them.

Even at below-market rates the bonds were adrenaline to Reserve Bank earnings. The Atlanta Fed saw its government securities portfolio burgeon from nothing in 1915 to $19.5 million by 1918. Earnings, fed by the securities, were strong enough in 1917 for the Bank to pay all dividends due and still have $80,000 left, of which $40,000 was used to start a surplus account and $40,000 paid to the Treasury as a franchise tax, the Bank's first transfer of earnings to the federal Treasury. From 1919 earnings the Bank was able to put $3 million in its surplus. It was thriving at last. "The increase of nearly every item on the balance sheet for 1919 is an indication of the increasing use by member banks of the facilities offered by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta," the 1919 annual report noted with satisfaction.

The expansion of the balance sheet and earnings was accompanied by an expanding level of activity inside the Bank. Not only was credit activity booming by 1919, but the fiscal agency work load had mushroomed as Reserve Banks warehoused the government bonds which by then were being sold to the public, at market yields, in Liberty Loan drives. The Reserve Banks took care of sending bonds out to member banks and redeeming them at maturity. Once the United States entered the war in 1917, several of the Atlanta Fed's employees left to join the army, creating a manpower crunch. One employee who remained at the Bank, Henry Frazer, recalls the busy days of 1919 this way: "At the close of World War I clerical help was nearly impossible to obtain or retain. As a consequence we started work at 8:30 a.m., and rushed to finish the day's work in time to catch the last street car of the evening. . . . Normally the notes were not delivered to the typing unit until around 4 p.m., and it was rush, rush, rush to get the work completed, checked, balanced and filed. You had a wonderful feeling all during 1919 when you could pause, grab your hat and run down the street to a 'hash joint' . . . to get a big lunch for 25 or 30 cents around 4 p.m. A sandwich or apple around 8 or 9 o'clock was your last meal for the day."

The vacated First Presbyterian Church of Atlanta was razed to accommodate construction of the Atlanta Fed's new head office. |

Max Wellborn takes command

The increased work load brought to light some problems in the organization and operation of the Atlanta Bank as well as disagreements between its two principal executives, Chairman Wellborn and Governor McCord. The Board in Washington conducted annual examinations of the operations of the 12 District Banks. Atlanta was deemed not up to snuff, and so W.P.G. Harding came to the December 1917 meeting of the Atlanta board to discuss the report by Federal Reserve Board examiners. "He called especial attention to the necessity of a thorough and competent organization," the minutes of that meeting state. He was particularly critical of the credit department. "Governor Harding said the law was plain, especially in regard to securing proper credit statements from member banks, and that the regulations must be enforced, and that the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta should not endeavor to popularize the institution by waiving the rules or regulations in this or other respects," the minutes record.

The following year did not bring improvements, and in 1918 John A. Will, the Board's chief Federal Reserve Bank examiner, told the Atlanta board "that he was very much disappointed at the conditions prevailing in certain departments of the Bank. . . . He stated further that the Bank had never had a thorough systematic organization," according to the minutes of the December meeting. Governor McCord, in the Bank's defense, noted that men going off to the war and a severe influenza epidemic had created high turnover in the staff.

Problems in managing the Bank brought into the open a conflict that had been simmering for a long time. Wellborn was unhappy with the leadership of McCord and with the limited authority of his own position. The division of duties between the chairman and governor was a topic repeatedly addressed by the Board in Washington and by these officials themselves. The governor supervised the operations of the Bank. The chairman presided over District board meetings, issued annual reports, saw that business statistics were compiled and, in his role as Federal Reserve agent, was the Board of Governors' representative in Atlanta. (As such, for instance, he officially received currency shipments from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and verified that the Reserve Bank had adequate collateral before transmitting the money to the Bank's custody.) As the System evolved the governor came to have the larger staff and the greater duties. In most of the Reserve Banks he was recognized as the chief executive. Wellborn is described by M.W. Bell, the Bank's cashier, who worked closely with both Wellborn and McCord for many years, as one "who could not be happy in any position of subordination to anyone else." Bell and others at the Bank thought that Wellborn and Governor Harding, who had recruited and supported him, believed that the chairman would be the dominant leader.

Whatever misjudgments may have been made, some changes were about to occur. After the December board meeting at which management of the Bank was criticized by examiner Will, director Frank Foote went to Washington in January to tell the Board that Wellborn should replace McCord as governor. When the Atlanta board met in February, Harding was present. The board went into executive session, and McCord, who was not a director, left the meeting.

McCord gave this account of what happened next: "Governor Harding then came to my office and stated that he did not see any solution of the matter except that I resign my position as Governor, and further stated that . . . he would immediately nominate me as Chairman. . . . I acted on Governor Harding's suggestion, and tendered my resignation." The board thereupon elected Wellborn governor, and McCord subsequently was elected chairman. With the switch, Wellborn took charge of the daily management of the Bank while McCord assumed the more ceremonial functions, an uneasy arrangement that lasted until 1924.

A change of address

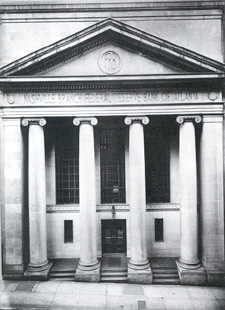

The increased activity and growing income of the Bank created both the need and the means for expansion. The Bank's original quarters in the Hurt Building were elegant and secure but suddenly cramped in light of the wartime expansion of the Bank's operations. By April 1916 a committee was prospecting for sites for a new building. It found one on Marietta Street, almost opposite Cone Street, a spot recently vacated by the First Presbyterian Church. The property was acquired from the church for $102,500 in October 1916. The old church building was torn down and construction begun on a new Federal Reserve Bank building in 1917. Although subsequent additions and rebuilding programs have replaced virtually all of the original building, the Bank has continued to occupy this site since it first moved there on October 1, 1918.

The board of the Atlanta Bank voted for construction of a new building on the Marietta Street site at its January 1917 meeting, at a cost not to exceed $200,000. An attractive new building, Atlanta leaders told the Board in Washington, would help to attract more state-bank members. The Board scaled back the budget to $175,000. Observed Governor Harding in a letter to Wellborn, "The Board believes that [the] cost might be reduced without modifying the lines of the building by cutting out florid decorations. . . . The lobby as proposed in your plans is larger than that of the New York Bank and it seems to the Board that it is really larger than need be and valuable space wasted thereby."

Governor Harding also observed that the interest on the debt for the new building would exceed the rent paid for the Hurt Building quarters and urged that approval for the new building be linked to a push to bring in more state banks as members of the System. "[E]very effort should be made before the final contracts are let, to secure the applications for membership of some of your more important state banks," he suggested, remembering how Atlanta leaders had told the Organization Committee that "many of the large state banks in Georgia would at once come into the system, but so far not one of them has." It was time, he concluded, "to put every pressure upon prominent state banks to apply for membership." Whatever the reason, there was a significant influx of state banks onto the membership rolls between 1916, when there were just 4, and 1920, when there were 87.

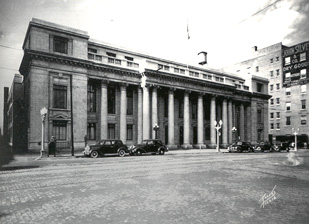

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta building as it looked in the 1920s. |

The building itself, designed by Atlanta architect A. Ten Eyck Brown, was a two-story granite structure "of thoroughly modern construction," according to Governor McCord. It even included a Lamson Pneumatic Tube System. "While the new quar- ters are adequate for the bank proper at present," McCord wrote in the 1918 annual report, "additional space will have to be provided in the near future, as the business of the institution is rapidly increasing and it is now necessary to operate the fiscal agent department in a nearby building."

McCord's predictions proved correct, and the first half of 1919 was spent planning additions to the new building. A third floor was added, including a directors' room, committee rooms, and space for auditors and files. A three-story-plus-basement annex building was built on the rear of the first building, to house the currency, transit, fiscal, and discount departments, files, rest rooms, and a cafeteria. The additions, also designed by Ten Eyck Brown, cost $200,000 and were completed in the summer of 1920. Further expansion doubled the building in 1923. As this third addition in four years was nearing completion, the subject of fine art came under consideration, and Atlanta painter Wilbur Kurtz was commissioned to depict the signing of the Federal Reserve Act. That sole portrayal of the historic event hung in the directors' room and then the cafeteria of the Bank before being donated to the Woodrow Wilson Birthplace Foundation in Staunton, Virginia. It hung for many years in the Federal Reserve headquarters building in Washington, and hangs there again in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the System, on loan from the Wilson Foundation.

The tree Branches

Not all of the Bank's building occurred in Atlanta. The Federal Reserve Act did not provide for Branches of Federal Reserve Banks, but demand did. The System's first Branch was opened in New Orleans on September 10, 1915, a somewhat unusual move in light of the slow start the System was experiencing but one dictated by the fact that New Orleans was the nation's 19th largest city and the largest in the South to be denied a Federal Reserve Bank. It was nearly 500 miles from Atlanta, making it difficult to serve, and the city's banks were clamoring for at least a Federal Reserve facility and guaranteed to pay the Branch's expenses during its first year of operation. Serious discussion of a New Orleans Branch took place during December 1914, the Bank's second month of operation, and the board officially recommended such a Branch at its January 1915 meeting. The Branch was first located in the U.S. Trust and Savings Bank building on Camp Street, and, in operations, was practically a duplicate of the Atlanta Bank.

Demand for other Branches followed. Bankers from Birmingham and Nashville attended a March 1918 board meeting to petition for Branches in their cities, and Jacksonville bankers sent a telegram. Branches were opened in Birmingham and Jacksonville

The Nashville Branch opened in 1919. |

on August 1, 1918, and in Nashville on October 21, 1919. These Branches were modeled after the limited Branches which had been established in Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, rather than the more empowered New Orleans Branch. Space for the Branches was rented in local bank buildings: in the Jefferson County Bank Building in Birmingham, in the Atlantic National Bank Building in Jacksonville, and in the First and Fourth Bank Building in Nashville. Savannah banks lobbied for a simpler agency office in that city (primarily for currency and fiscal agency services) and got one in February 1919. Chattanooga wanted an agency, too, but the board decided that one was unnecessary. Only two more satellite offices would be added in the Bank's first 75 years—in Havana, Cuba, and Miami. Otherwise, the expansion of Reserve Bank offices in the Sixth District had been concluded by 1920.

In light of increased activity and solid earnings during the 1920s the Board in Washington was willing to see Branches established in larger, permanent quarters. Contracts were signed in 1922 for construction of a $706,400 four-story-and-basement building in New Orleans (at the corner of Carondelet and Common Streets) and for a $191,700 two-story building in Jacksonville (at Hogan and Church Streets). The $215,700 three-story Nashville building on Third Avenue North was completed in December 1922, and in 1925 plans were approved for a $290,000 building for Birmingham.

| Previous | Next |