Although the labor force participation (LFP) rate has fallen significantly for the overall population during the past two decades, the trends can differ a great deal depending on which demographic group you examine. One way to view these varied, ever-changing patterns is to use the Atlanta Fed's Labor Force Participation Dynamics tool. We recently redesigned the tool, adding a new interface and more options for understanding specific demographic groups' LFP. The tool also allows users to see what factors (such as disability/illness, being in school, retirement, or family responsibilities) influence changes in the LFP rate for different groups.

While the tool shows us many stories, a particularly interesting one is the experience of people of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race (henceforth referred to as Hispanic). Hispanics are a growing share of the U.S. population (the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] projects that nearly a fifth of the people in the labor force will be Hispanic by 2024, up from a tenth in 1994), and therefore Hispanics' differences in attitudes and preferences for work will exert an increasingly great effect on headline LFP numbers.

Let's parse the LFP rate among Hispanics. First, the Hispanic population is more likely to engage in the labor force than non-Hispanics. (In 2017, the LFP rate of Hispanics was 66.1 percent, compared to 62.2 percent for non-Hispanics). Second, their LFP has fallen by less during the past two decades.

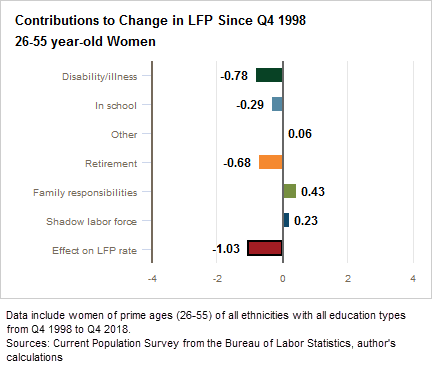

The pictures below come from the redesigned tool. The first two charts compare the decline in the LFP rate for all ethnicities (Chart 1) versus Hispanic (Chart 2) as the combination of six nonparticipation categories. Each colored bar represents how much a particular category of nonpartipation has changed since the fourth quarter of 1998. The red line shows the summation of the change in each nonparticipation category, or the net change in the LFP rate. For example, the LFP rate overall has declined 4.2 percentage points (ppts) during the past two decades. However, among Hispanics, it has fallen significantly less—just 1.0 ppt. A comparison of the size and direction of each of the nonparticipation categories between the two charts shows many differences in the factors affecting the decline in the LFP rate of each group.

Because differences across ethnicity could reflect differences in their age distributions—Hispanics are younger on average than the population as a whole—it is important to control for this difference. Using the tool, it's easy to narrow this comparison to look specifically at 26–55 year olds.

In particular, the LFP rate for women of all ethnicities from 26 to 55 years old has declined by 1.0 ppt since 1998. In sharp contrast, the LFP rate for Hispanic women 26 to 55 years old has actually increased by 3.8 ppts. Compared to 20 years ago, this group is less likely to say they don't want a job because of disability/illness (1.1 ppt) and family responsbilities (1.4 ppt). This group is also less likely to be part of the shadow labor force (1.4 ppt) compared to two decades ago. (The shadow labor force, as we define it, is made up of individuals who say they want a job but are not considered unemployed by the BLS.) This article from the BLS delves into more detail about Hispanics in the labor force.

The LFP tool allows you to explore many other labor force stories. Users can cut the LFP data by three education categories (less than a high school degree, high school or some college, or associate's degree or higher), two age groups (26–55 or all ages), three race/ethnicity categories (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, and Hispanic) and for men and women. One thing that the tool makes clear is that the factors that influence individual decisions to work, look for work, or to pursue other activities vary across demographic groups, and each group's experience contributes to our understanding of movements in the overall LFP rate.

By

By