Editor's note: We have updated macroblog's location on our website, although archival posts will remain at their original location. Readers who use RSS should update their feed's URL to https://www.frbatlanta.org/rss/macroblog.aspx. Also, we are implementing a new commenting system for posts. In the comments section at the end of this post, you'll be able to create an account to leave comments.

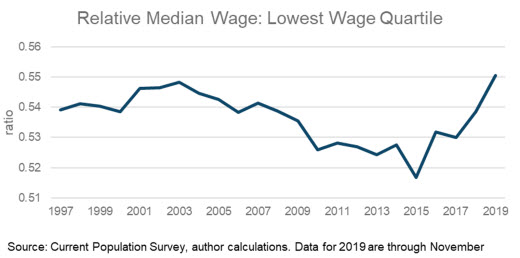

A recent macroblog post used Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker data to observe that the hourly wage of the lowest-paid workers has rebounded in recent years after declining for a decade. The chart below depicts this finding, showing the median hourly wage of the lowest-paid 25 percent of workers in the Tracker sample relative to the median for all workers.

Moreover, the post showed that this recovery was not just a story about states and localities increasing their minimum wages. It also appears that there has been a significant tightening in the labor market for unskilled or low-skilled jobs.

Taken at face value, this is good news for workers employed in low-wage jobs. But here's the rub: the median wage in the first quartile is still low—$11.50 in 2019, or 55 percent of the overall median wage. Moreover, these are hourly wages before taxes and transfers (we'll get back to this shortly). They don't represent what is happening to these workers' ability to make ends meet, which depends crucially on income after taxes and transfers.

For households at the bottom of the income distribution, means-tested transfers can play an especially important role. Means-tested transfers—cash payments and in-kind benefits from federal, state, and local governments designed to assist individuals and families with low incomes and few assets to meet their basic living needs—represent about 70 percent of income before taxes and transfers for households in the bottom quintile of the income distribution, according to a recent report by the Congressional Budget Office. However, the size of the transfers tends to decrease as earnings increase, and they stop altogether when a worker exceeds income- and asset-eligibility thresholds.

The interaction between changes in earnings and various means-tested public assistance programs is an important public policy issue, and it is one that staff at the Atlanta Fed are studying. In a March 2019 macroblog post, David Altig and Laurence Kotlikoff reported that this interaction results in low-income households facing a higher median effective marginal tax rate than high-income households. For low-income households with children, this effect can be especially severe because the presence of children increases the value of programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (or SNAP, formerly known as the food stamp program) and the likelihood of enrollment in additional programs such as federally subsidized child care. (You can read further research on the effective or implicit marginal tax rates of low-income households at Congressional Budget Office (2016), Romich and Hill (2018), and Chien and Macartney (2019).)

To illustrate the point, the Atlanta Fed team studied the case of a hypothetical single mother with two young children who works in a near-minimum-wage, full-time job and whose basic living expenses are helped by various transfer programs. One avenue to improving her family's standard of living is if she were to return to school and pursue a higher-paying career as a nurse. Over the long term, the net gains from education and career advancement are unambiguous. However, the Atlanta Fed's analysis shows that as long as her children still require care, the reduction in payments from various benefit programs could partially or even completely offset the gains. Look for an Atlanta Fed paper discussing this very real dilemma coming soon on the Bank's Economic Mobility and Resilience webpage.

What do findings like this mean for interpreting the Wage Growth Tracker's evidence that people in the bottom part of the wage distribution are experiencing relatively larger wage gains? Perhaps there is a bit less to celebrate than meets the eye. Around 46 percent of these individuals are in households with children. To the extent that they also participate in means-tested public assistance programs, the relative increase in their family's standard of living could be much less than the size of their pay raise would suggest.

By

By