The national housing market is generally rebounding in the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis and economic downturn, but the outlook varies in local housing markets.1 In some southeastern cities, there are housing submarkets that are becoming increasingly "hot." Recently, the Wall Street Journal reported that Nashville was among 10 regions in the country with the strongest rent growth in the second quarter of 2014 compared to the first quarter.2 The city's population has increased by 2 to 3 percent each year for the last several years, catalyzing residential construction and escalating housing values. Meanwhile, Atlanta's BeltLine (one of the nation's largest transit-oriented development initiatives) is driving up nearby property values and speculative investment activity significantly.3 Some coastal cities in Florida–which were hard hit during the foreclosure crisis–have seen housing values rebound.4

The national housing market is generally rebounding in the aftermath of the foreclosure crisis and economic downturn, but the outlook varies in local housing markets.1 In some southeastern cities, there are housing submarkets that are becoming increasingly "hot." Recently, the Wall Street Journal reported that Nashville was among 10 regions in the country with the strongest rent growth in the second quarter of 2014 compared to the first quarter.2 The city's population has increased by 2 to 3 percent each year for the last several years, catalyzing residential construction and escalating housing values. Meanwhile, Atlanta's BeltLine (one of the nation's largest transit-oriented development initiatives) is driving up nearby property values and speculative investment activity significantly.3 Some coastal cities in Florida–which were hard hit during the foreclosure crisis–have seen housing values rebound.4

While no one is missing the conditions experienced during and after the downturn—including lost housing equity or blighted foreclosed properties—the "heat" of the current and forecasted housing market is introducing a different crisis: on-the-ground housing specialists are saying that the demand for affordable housing is far outpacing supply. Some southeastern cities are likely to face an affordable housing crisis since local conditions are on the brink of the "affordability tipping point." This tipping point occurs when the private market no longer provides an adequate supply of lower-cost housing affordable to households at or below the median household income.

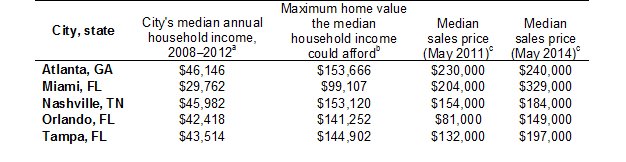

The tipping point is partially explained by cities experiencing growth and no longer being able to rely upon sprawl to accommodate lower-cost housing needs.5 Consequently, economic and community development strategies such as downtown revitalization, urban infill, and transit-oriented development are taking hold in major cities in the Southeast, including Atlanta, Charlotte, Nashville, Jacksonville, and Orlando.6 Some observers wrongly equate increased density with improved affordability, as more housing units are thought to increase supply and therefore soften demand. However, the opposite is established in the research: density and its associated amenities, such as walkable communities and access to public transit, may result in rising property values if planning and development are not partnered with equitable land use policies and affordable housing interventions.7 It's not surprising that some cities are realizing an upswing in new residential construction,8 but rent and sale costs far exceed what is affordable for low- or moderate-income households (see the table).9 Essential segments of the workforce like teachers, police officers, medical personnel, and social service providers are increasingly "driving for affordability" or "driving until they qualify," which is exacerbating congestion and creating costly problems, such as the need to expand highway systems or fund additional infrastructure.

Median Household Incomes, Home Values, and Sales Prices in Five Southeastern Cities

a Source: U.S. Census Quick Facts. Median household income is for the city and not the metropolitan statistical area (MSA).

b Housing cost burden is commonly defined as spending no more than 30 percent of the household's income on housing costs. Therefore, the maximum home value multiplies the median household income by 3.33. This number is an overestimate, as it does not take into account principal, interest, taxes, and insurance or nonhousing debt.

c Source: Zillow Home Value Index for all homes within the city, rounded to the nearest $1,000.

Adding to the crisis, communities across the country are beginning to feel the impact of substantial cuts in federal programs for affordable housing. Since 2010, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) HOME funds and Community Development Block Grant Program funds have decreased by 45 percent and 30 percent, respectively. Other HUD and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) programs have already suffered budget cuts.10 At its peak, federal funding was inadequate to meet affordable housing needs. There is no evidence to suggest that these federal programs will return to prerecession funding levels, so state and local jurisdictions will have greater responsibility for addressing affordable housing needs.

Unlike many of their northern counterparts that passed the affordability tipping point long ago, most states and cities in the Southeast have not established public policies and plans, infrastructure, and resources to address the looming affordability problem. Local housing practitioners have indicated that few southeastern states or cities have robust inclusionary zoning policies, housing trust funds, land banks, and permanently affordable housing programs. Thus, these cities are at risk of experiencing less access to a large segment of the workforce, sprawling development patterns, increased traffic congestion, air quality issues, and declining racial and economic diversity.11 In the long term, these cities may face out-migration, losses to the tax base, and increased geographic segregation.12 Before these adverse effects fully set in, states and cities can explore strategies to prioritize the production and preservation of more affordable housing.

Inclusionary housing: one viable solution

Some larger cities in the Southeast have housing markets that offer insufficient affordable options for lower-income residents.13 A strategy for these cities is to adopt and implement inclusionary housing policies—local land use policies that link jurisdictional approvals for construction of market-rate housing to the creation of affordable homes for low- and moderate-income households. Inclusionary housing policies are sometimes referred to as "inclusionary zoning." Inclusionary policies typically require or incentivize that housing developers support the creation of a certain percentage of affordable units. In return, the municipality typically provides nonmonetary compensation (an indirect subsidy) to residential developers in the forms of density bonuses, zoning variances, expedited permitting, and cost offsets through tax breaks or fee reductions.

The primary goals of inclusionary housing programs are to expand the supply of affordable housing and promote social and economic integration.14 The vast majority of inclusionary housing programs are designed not only to produce affordable homes but also preserve a stock of housing that remains affordable over time. Production and preservation of affordable homes are critical for creating inclusive communities and addressing housing needs among families with modest incomes.

Notably, inclusionary housing is a unique and potent tool in the affordable housing "tool box." It leverages the strengths of the local for-profit development industry and ensures the community receives benefit from public investments that support private market development. For-profit developers often capitalize on existing public investments in infrastructure (parks, public transit, and schools) and additional public incentives are provided in exchange for affordable units (density bonuses, zoning variances, and cost offsets). Consequently, inclusionary housing programs require that some of the profit derived from public policies and investments is recaptured for public benefit. Inclusionary zoning policies ensure that for-profit developers are able to make an adequate profit and sometimes a larger profit than base zoning would allow. However, these policies concurrently help to minimize adverse impacts on low- and moderate-income families, neighborhoods, and the community at large.

Additionally, effective programs can produce a significant number of affordable homes and preserve them as a vital part of the housing stock. Because the production of affordable housing is often linked to sites where the private market is investing, the result is that these affordable units tend to be located in gentrifying areas or asset-rich neighborhoods. Therefore, inclusionary housing may result in improved access to better schools, public transit, job sites, food options, and other place-based benefits for working families. New residential construction tends to be high-quality, energy efficient, and include amenities; thus, well-designed inclusionary housing programs result in high-grade affordable units that are reputable within the community. Finally, because the success of for-profit residential development companies is contingent upon accurately predicting supply and demand, affordable units created through inclusionary housing programs are often highly marketable and meet local housing needs.

Based upon the individual and collective benefits resulting from these private-public partnerships, it is perhaps unsurprising that inclusionary housing is significantly expanding across communities in the United States. A recent study conducted by the National Housing Conference's Center for Housing Policy and National Community Land Trust Network and published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy documented 507 inclusionary housing programs in 487 jurisdictions located within 27 states and the District of Columbia.15

While 78 percent of these programs were located in New Jersey, California, and Massachusetts (which have state laws that incentivize or require meeting a specified share of affordable housing), a growing number of inclusionary housing programs are located in coastal states, the Midwest, the Rocky Mountain West, and the Southeast. For instance, North Carolina has at least 10 programs throughout the state.

The literature on inclusionary housing policies and programs continues to grow. Evidence suggests that inclusionary zoning policies promote inclusive communities by locating affordable housing in low-poverty, high-opportunity neighborhoods. A study of 11 localities across the country with inclusionary housing programs found that affordable units were widely dispersed throughout jurisdictions and located in neighborhoods and assigned to schools with lower poverty rates than other affordable housing.16 Other studies have supported that inclusionary housing programs have promoted racial and economic integration throughout jurisdictions.17

Evidence also strongly supports that voluntary programs produce significantly fewer (or hardly any) units relative to mandatory programs.18 National research has found that 83 percent of all U.S. programs had mandatory policies; voluntary programs tend to be more prevalent in the Southeast (in Tennessee, Georgia, and Florida).19 Well-designed policies can lead to significant production. For example, information available from 2002 to 2004 suggests that 10 percent of all newly constructed homes in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, became permanently affordable due to the inclusionary policy.

Research also shows that most inclusionary housing programs are preserving the affordability of units over time. The national study found that 81 percent of 306 inclusionary programs (for which information was available) require that rental units remain affordable for at least 30 years, and 84 percent of 327 programs (for which information was available) require that homeownership units remain affordable for at least 30 years. The majority of these inclusionary programs—for both rental and homeownership—are designed to provide permanent affordability. Older programs tended to have longer affordability durations or opted to revise their policies for longer affordability requirements after recognizing the importance of affordability preservation to reach objectives and minimize attrition of affordable units over time.20

Critics of inclusionary zoning have speculated that these programs may result in significant decreases in residential production and increases or decreases in housing values.21 However, rigorous studies have found little or no impact on the overall housing supply or prices of market-rate homes. For example, one study in California found that the volume of new single- and multifamily construction was not affected by the adoption of inclusionary zoning policies.22 More recently, another study in California found that inclusionary housing programs had insignificant effects on housing starts and small effects on single-family prices of 2 to 3 percent.23 Other research found no evidence of inclusionary zoning affecting single-family starts or prices in San Francisco, while inclusionary housing in Boston was associated with very small declines in single-family production and small increases in single-family pricing.24 Continued research is needed to better understand how inclusionary policies affect housing markets that are just now reaching the affordability tipping point.

Ultimately, the impact and outcomes of any inclusionary housing program is largely contingent upon the design of its policies and program. A central finding of literature reviews on inclusionary housing is the expansive variation in policy and implementation.25 No one inclusionary zoning ordinance or inclusionary housing program is designed the same way, as they must be tailored to local housing market trends and conditions. Well-designed policies and programs are able to partner productively with for-profit developers to yield a significant stock of affordable housing that is preserved over time to ensure communities become and remain inclusive.

Conclusion

How imperative is it for southeastern cities with strong housing markets to adopt well-designed and well-implemented inclusionary housing programs? Trends suggest the demand for affordable housing has never been greater. Inclusionary housing is one suitable approach in this region since it does not require direct subsidy dollars to create affordable homes. Waiting to address affordable housing production and preservation in strong-market southeastern cities will only become more costly and difficult as density and property values increase.

For further reading on how to design and implement a successful inclusionary housing program, additional resources are provided below. Successful programs require strong partnerships and support from for-profit developers, lending institutions, and often nonprofit organizations (such as community land trusts) that have the capacity and expertise to support program administration and ensure affordability is preserved. The resources also address the process and considerations for building successful partnerships within a community interested in pursuing this option.

Additional resources

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Real Estate Research blog.

Robert Hickey, Lisa Sturtevant, and Emily Thaden. Achieving Lasting Affordability through Inclusionary Housing, Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, July 2014.

National Community Land Trust Network's Resources on Developing an Inclusionary Housing Policy:

Part I. Key Considerations for the Policy and Regulations

Part II. Key Consideration for the Homeownership Program

Sample Documents Library

C. Tyler Mulligan and James L. Joyce. Inclusionary Zoning: A Guide to Ordinances and the Law, Chapel Hill, NC: School of Government, University North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2010.

Center for Housing Policy publications on inclusionary zoning:

http://www.nhc.org/publications/Inclusionary-Zoning.html

By Emily Thaden, research and policy development manager of the National Community Land Trust Network, and Emily Mitchell, Atlanta Fed CED senior analyst

_____________________________________________________________

1 The State of the Nation's Housing 2014, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, 2014.

2 "Nashville Rent Increases Have Residents Singing the Blues," Chelsey Dulaney, the Wall Street Journal, Aug. 10, 2014.

3 The Role of Community Land Trusts in Fostering Equitable, Transit-Oriented Development, Robert Hickey, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, June 2013.

4 Percent Change in Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) MSA-Level House Price Indexes, FHFA, 2014. Coastal Florida MSAs were reviewed, including Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater and Miami-Miami Beach-Kendall MSAs.

5 Rethinking U.S. Rental Housing Policy, Bruce Katz and Margery Austin Turner, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, March 2007 and "Home Prices and Population Growth: Cities vs. Suburbs," Jed Kolko, Trulia, April 10, 2014.

6 Complete Streets in the Southeast: A Tool Kit, Stephanie Seskin, Colin Murphy, Laura Searfoss, Craig Chester, Washington, DC: AARP, March 2014.

7 The Link between Growth Management and Housing Affordability: The Academic Evidence, Arthur C. Nelson, et al., Brookings Institution, February 2002.

8 "New Residential Construction," U.S. Census Bureau News Joint Release with U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

9 "New Home Prices by Metro Area and State," Natalia Siniavskaia, Eye on Housing, National Association of Home Builders, July 9, 2014.

10 FY15 Budget Chart for Selected Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and Department of Agriculture Programs, National Low Income Housing Coalition, June 9, 2014.

11 Measuring Sprawl and Its Impact, Reid Ewing, Rolf Pendall, and Don Chen, Smart Growth America, 2002.

12 How Housing Matters Research Briefs, MacArthur Foundation, April 24, 2014.

13 America's Rental Housing: Evolving Markets and Needs, Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University, 2013; "Despite Rising Home Values, Affordability Remains Largely Intact for Buyers," Svenja Gudell, Zillow Real Estate Research, Aug. 20, 2014.

14 Achieving Lasting Affordability through Inclusionary Housing, Robert Hickey, Lisa Sturtevant, and Emily Thaden, Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, July 2014.

15 Ibid.

16 Housing Policy Is School Policy: Economically Integrative Housing Promotes Academic Success in Montgomery County, Maryland, Heather Schwartz, New York: The Century Foundation, 2010.

17 The Effect of Inclusionary Zoning on Racial Integration, Economic Integration, and Access to Social Services: A Davis Case Study, Alexandra Holmqvist, master's thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2009; "Land Use and Housing Policies to Reduce Concentrated Poverty and Racial Segregation," Myron Orfield, Fordham Urban Law Journal 33(3): 101–159, 2005.

18 Voluntary or Mandatory Inclusionary Housing? Production, Predictability, and Enforcement, Nicholas Brunick, Lauren Goldberg, and Susannah Levine, Chicago, IL: Business and Professional People for the Public Interest, 2003; "Can Inclusionary Zoning Be an Effective and Efficient Housing Policy? Evidence from Los Angeles and Orange Counties", Vinit Mukhija, Lara Regus, Sara Slovin, and Ashok Das, Journal of Urban Affairs 32(2): 229–252, May 2010.

19 Achieving Lasting Affordability through Inclusionary Housing.

20 Ibid.

21 "'The Economics of Inclusionary Zoning Reclaimed': How Effective Are Price Controls?" Benjamin Powell and Edward Stringham, Florida State University Law Review 33, 471–499, 2005.

22 City of Los Angeles Inclusionary Housing Study, David Paul Rosen & Associates, prepared for Los Angeles Housing Department, September 25, 2002.

23 Housing Market Impacts of Inclusionary Zoning, Gerrit-Jan Knapp, Antonio Bento, and Scott Lowe, College Park, MD: National Center for Smart Growth Research and Education, February 2008.

24 31 Flavors of Inclusionary Zoning: Comparing Policies from San Francisco, Washington, DC, and Suburban Boston, Jenny Schuetz, Rachel Meltzer, and Vicki Been, Journal of the American Planning Society 75, Issue 4, 2009. Working Paper 08-02. New York, NY: Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy.

25 Achieving Lasting Affordability through Inclusionary Housing.