Contract for deed home sales, or installment contracts financed by sellers, have the potential to affect low-income homeownership in various ways. Between 2008 and 2013, corporate contract for deed sales sharply increased; they plateaued or slightly declined since that time in four southeastern metropolitan areas studied (Atlanta, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; Jackson, Mississippi; and Jacksonville, Florida). There are several reasons to pay attention to these sales:

- The contract for deed has the potential to benefit lower-income and lower-wealth buyers through its ability to make homeownership a possibility for those who cannot access the standard mortgage credit market.

- Still, many corporate-held contracts contain undesirable provisions, such as high interest rates, inflated purchase prices, and unfair forfeiture clauses.

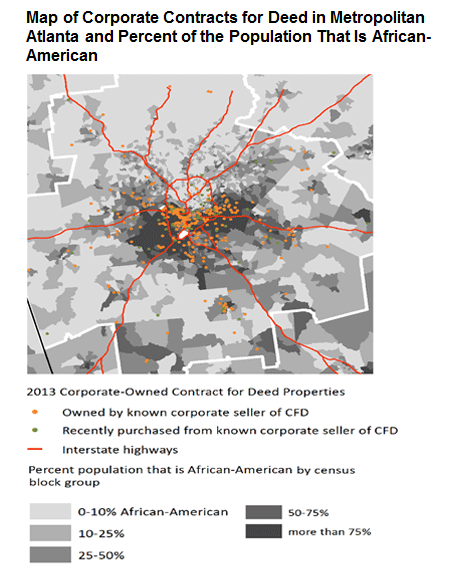

- These properties tend to be located in majority-African-American neighborhoods with less access to financial services.

These observations on contract for deed sales and the contracts' terms are presented in the recent Atlanta Fed discussion paper "Informal Homeownership Issues: Tracking Contract for Deed Sales in the Southeast" by senior community and economic development adviser Ann Carpenter, former CED intern Abram Lueders, and intern Chris Thayer. The paper details this practice, its recent trends, and its role in homeownership, particularly for low-income homebuyers.

What are contracts for deed?

Contracts for deed are a form of seller financing for borrowers who often cannot access standard credit markets due to their perceived risk (Perlberg, 2016). These borrowers, who are disproportionally low-income and members of ethnic and racial minorities, cannot employ the financial and legal services of the formal homeownership and mortgage financing process, and therefore look elsewhere to purchase a home (Way, 2009). In a contract for deed, the would-be homeowner may make a down payment and agree to monthly payments to the seller, but the person does not receive immediate title (ownership) of the house in return. Instead, the buyer has all the responsibilities of homeownership without any attendant privileges until the final payment is made. If the buyer falls behind in the payments at any point, he or she can be evicted under a commonly included forfeiture clause—retaining neither the down payment nor any of the equity built through the monthly installment payments or home improvements.

What do we know about contracts for deed in the Southeast?

The U.S. Census Bureau's American Housing Survey collected data on contracts for deed biennially starting in 2001. However, this question was eliminated from the survey in 2009, leaving few available data sources for tracking contract for deed activity, particularly at the national level.

The Atlanta Fed used historical CoreLogic real estate tax data to track ownership of properties in the Southeast by corporate sellers identified in recent reports. Corporations buying and selling properties as contracts for deed were identified based on previous investigative journalism (for example, see Goldstein and Stevenson, 2016 and Kanell, 2016). Four southeastern metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Birmingham, Jackson, and Jacksonville) with the highest number of residential properties owned by corporate contract for deed firms in 2015 were selected for analysis.

One state also provided a more complete picture of contracts for deed at large. Alabama requires that contracts for deed be recorded, and Jefferson County (which includes Birmingham) provided an online county database with full information on contracts from 1987 to the present. Detailed data on Jefferson County contracts also offered a number of other insights, including the likely gaps in recording of contracts for deed (even in a state where such recording is mandatory), and the proportion of contracts likely to have one or more buyer-unfavorable terms (roughly one-third of all contracts reviewed). Finally, examination of Jefferson County contracts showed that the majority of contract for deed sellers are private individuals or small businesses rather than corporate sellers.

What are consequences of a possible increase in contracts for deed?

Contracts for deed can have a number of potential consequences, depending on the way the contract is structured. If the contract is unfavorable toward the buyer and increases the risk of default, there are both community and individual impacts.

Lower-resourced neighborhoods were hit particularly hard by the foreclosure crisis, creating a large supply of low-cost foreclosed properties attractive to contract for deed investors. Based on the Atlanta Fed's analysis, neighborhoods with corporate contracts for deed are disproportionately African-American (see the map) and with fewer bank branches per capita than the area average. Contracts for deed with buyer-unfavorable terms are more likely to fail and can increase the eviction rate in these neighborhoods, thereby increasing school turnover and overall community instability. These homes, many of which have condition issues, may then lie vacant and further destabilize the community.

Sources: 2010–14 U.S. Census American Community Survey, staff calculations based on 2013 CoreLogic tax data

Homeownership is a key path to wealth building, and lower rates of homeownership by African-American households is a major contributor to the growing racial wealth divide (Asante-Muhammed, Collins, Hoxie, & Nieves, 2016). Contracts for deed with high-risk terms, including many corporate contracts for deed, can exacerbate these issues, capturing an already-vulnerable market segment and preventing the growth of equity and therefore, family wealth. "Habitable condition" clauses—which require the buyer to make significant repairs to often-distressed homes within a short time frame—especially limit the ability to build home equity and wealth. Research has shown that the cost of repairs can be a major barrier to sustained low-income homeownership (Van Zandt and Rohe, 2011) and contract clauses requiring extensive repairs can similarly undermine stable homeownership. When contracts for deed have unfavorable terms such as a forfeiture clause, homeownership can become very difficult to sustain.

How to protect consumers

The National Consumer Law Center (Battle et al., 2016) recommends a number of practices to protect contract for deed buyers, such as a legal requirement to record, disclosures of interest rates and fees, independent inspection of the home's condition including estimated cost of repairs, a third-party appraisal to ensure fair market value of the property, standardization of documentation, an assurance that all taxes and liens on the property are resolved prior to sale, the right to prepay without penalty, protection in case of early termination of the contract (by both buyer and seller), prohibition of abusive and unfair practices, translation of documents in the buyer's language, strong enforcement of all policy recommendations, and greater data collection, potentially through the expansion of data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (Battle et al., 2016). With these consumer protections, the contract for deed structure can be a helpful tool to increase low-income access to homeownership. Read the full paper for a better understanding of conditions in the four southeastern metros.

By Chris Thayer, an intern in the community and economic development group

References

Asante-Muhammed, D., Collins, C., Hoxie, J., & Nieves, E. (2016). The Ever-Growing Gap: Without Change, African-American and Latino Families Won't Match White Wealth for Centuries. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Studies and CFED.

Battle, J.J., Mancini, S., Saunders, M., & Williamson, O. (2016). Toxic Transactions: How Land Installment Contracts Once Again Threaten Communities of Color. Boston, MA: National Consumer Law Center.

Galante, C., Reid, C., & Sanchez-Moyano, R. (2017). Expanding Access to Homeownership through Lease-Purchase. Washington, DC: J. Ronald Terwilliger Foundation for Housing America's Families.

Goldstein, M., & Stevenson, A. (2016, February 21). "Market for Fixer-Uppers Traps Low-Income Buyers." New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/21/business/dealbook/market-for-fixer-uppers-traps-low-income-buyers.html

Kanell, M. (2016, July 14). "Dallas Firm Targets Atlanta Minorities in Housing, Report Says." Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved from http://www.ajc.com/business/dallas-firm-targets-atlanta-minorities-housing-report-says/HyLdCDsPg8RyC2SRI8bD0H/

Perlberg, H. (2016). "Apollo's Push into a Lending Business That Others Call Predatory." Bloomberg. Retrieved from: http://www.nreionline.com/finance-investment/apollos-push-lending-business-others-call-predatory

Van Zandt, S., & Rohe, W. (2011). "The Sustainability of Low-Income Homeownership: the Incidence of Unexpected Costs and Needed Repairs among Low-Income Home Buyers." Housing Policy Debate 21(2), 317–41.