The seemingly abrupt arrival of COVID-19 and the ensuing public health need to "flatten the curve" has had a significant impact on the U.S. economy. The enforcement of social distancing policies, mandatory business shutdowns, and shelter-in-place orders have left many small business owners vulnerable to permanent closure. This article offers an overview of the state of small businesses in the Southeast pre-COVID-19, explores the virus's impact on small businesses and the communities in which they are located, and suggests some potential paths forward to support small businesses.

Small businesses in the Southeast

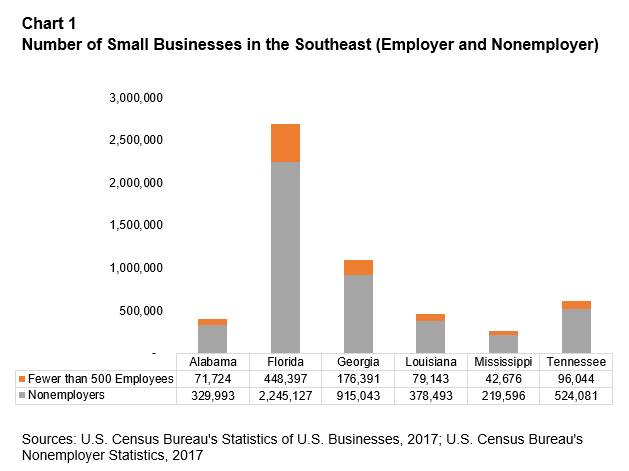

Small businesses (firms with fewer than 500 employees) serve as the lifeblood of the economy. They help drive innovation and competitiveness, accounting for 44 percent of U.S. economic activity.1 The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's Sixth District2 is home to over 5.5 million small businesses, which employ 43.8 percent of all workers in the Southeast and represent 97.9 percent of all employer firms (see charts 1 and 2). In some parts of the region, small businesses play an even larger role in the local economy; for example, small business is responsible for over 50 percent of all jobs in Louisiana (see chart 3). While small business ownership has challenges—only 45 percent of businesses have a five-year survival rate—small businesses allow people to create their own jobs, sometimes when the traditional labor market fails them, and provide employment opportunities to others in their community.3

In the Southeast, minority-owned firms (we use the term "minority" to refer to non-White racial groups generally; when possible, we specify the particular ethnic or racial group) play an important role in the region's economy. Nationally, small minority-owned firms account for roughly 19.8 percent of all small businesses, compared to nearly 21.6 percent of all small businesses in the Southeast.4 The map displays the share of minority-owned small businesses across the Southeast by state, ranging from 26.5 percent in Florida to 11.5 percent in Mississippi.5 Research indicates that minority entrepreneurship can significantly reduce the racial wealth gap while simultaneously reducing minority unemployment as these firms tend to hire neighborhood residents.6,7

Small businesses and COVID-19: voices from the field

The challenges small businesses are facing today are magnified by the uncertainty of near- and long-term impacts of COVID-19. To understand the challenges small businesses are facing and to support the development of solutions to those challenges, we conducted phone interviews in March and April of 2020. Interviewees were primarily community development financial institutions and other nonprofits that support smaller businesses. The interviewees collectively serve over 25,000 businesses in the Southeast.

Most immediately, interviewees indicated that the small businesses they are serving have limited time, from days to less than three weeks, to keep their doors open, given that a state-mandated shutdown or a significant fall in revenues was depleting their current financial reserves. There was a real concern that many of these businesses were at risk of permanent closure. One interviewee captured this concern by sharing the uncertainty of what recovery from COVID-19 will look like: "if this crisis looms, several of the small businesses we serve will not recover." National surveys have found similar results, with one noting that 2 percent of businesses had "permanently closed" in March, just a few weeks into the public health crisis.8

There was also general consensus among interviewees that the longer the crisis lingers, the longer the recovery will take for small businesses and the communities they depend on to thrive. They stressed an urgent need for funds to help small businesses. The top three immediate business needs, according to interviewees, included employee payroll, technical assistance to navigate both existing and new sources of funding, and other fixed costs.

Interviewees echoed a consistent theme that COVID-19 is amplifying disparities that existed in small businesses, and that assistance will not filter to the communities and people that need them the most. For example, interviewees expressed concern that the first round of the Paycheck Protection Program was primarily accessed by firms that had existing banking relationships. Respondents noted that smaller, minority, and younger firms are less likely to have these banking relationships and therefore are particularly vulnerable to closure. Several respondents wanted the recovery to forge more equitable economic outcomes. One interviewee noted, "We do not want to return to our economic condition pre-COVID, we want to be better."

To support a more equitable response and recovery, interviewees noted that targeted investments in historically disinvested communities would be required, including targeting underresourced rural areas and smaller businesses with less than 20 employees. As one interviewee noted: "When you live in isolated and disinvested communities, if all you have left operating is a farm, you don't have a functioning town anymore." Contacts saw small businesses as essential economic anchors to bolster such places or make them economically viable. Some interviewees noted that the communities they serve consistently trail economic recoveries. Generally, there was a shared sense that policymakers, lenders, and funders needed to take swift action to infuse small businesses with capital in order for them to survive.

The interviews also explored the current conditions of nonprofit small business providers and community lenders. Overall, organizations were experiencing significant disruption from COVID-19. The transition to remote work posed varying degrees of difficulties, with some nonprofits realizing they did not have all the necessary technology resources. In this new work environment, many organizations are grappling with how they provide direct services to small businesses virtually on top of increased demand for their services. The length of time these organizations believe they can operate in a contingency environment varies, mostly depending on funding. One interviewee noted that, "COVID has pushed, challenged, and strained smaller, underresourced, frontline organizations even harder."

Interviewees shared that, "It is too late for many of these small businesses, and there is interest to think about the third and fourth rounds of funding to help more small business owners and emerging entrepreneurs join a recovering economy." They saw opportunities to redefine, streamline, and create more aligned structures to support small businesses, particularly if philanthropic and public funding could be aligned and banks and community development financial institutions could establish strategic partnerships to accelerate the deployment of funds. Rather than focusing on one-time, short-term "disaster relief" funds, these service providers suggested focusing funds on the long-term recovery of small businesses.

Small businesses in hardest-hit industries

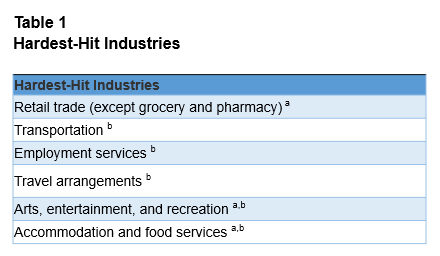

Following methodology developed by colleagues at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, this section further explores how COVID-19 has affected small businesses in the Southeast. The Philadelphia Fed identified six hardest-hit industries—sectors considered the most vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19—by compiling data from two sources. The first data source is a list of industries, in which a significant share of workers (over 40 percent) are in occupations that require close physical proximity to their customers or coworkers.9 The second data set comes from a research note by Moody's Analytics (2020), which identified industries at highest risk of lost revenues and vulnerability to layoffs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As table 1 shows, industries identified by these two approaches have significant overlap but also some apparent differences. This section focuses on the industries identified by these two sources, with the exception of construction and mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction.

Note: a indicates industries with larger shares of workers with high level of physical proximity by Wardrip and Tranfaglia (2020); b indicates industries categorized as most at risk in a research note by Moody's Analytics (2020). The mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction industry was hit hard by the collapse of oil prices that happened roughly at the same time as the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States, instead of by the COVID-19 pandemic itself. Although construction has a high level of occupational contact intensity, it is considered an essential industry by many states.

Based on this analysis, table 2 demonstrates that over one in four small businesses within southeastern states are in the hardest-hit industries, with the exception of Florida (24 percent), and the greatest representation in Mississippi (34 percent). Additionally, these small businesses in hardest-hit industries account for almost one-third of employment across the Southeast. Business shutdown orders had a broader reach beyond the hardest-hit industries. Moreover, small businesses outside mandated shutdown lists may have chosen to close voluntarily in response to COVID-19. The actual magnitude of affected small businesses, therefore, is likely greater than our estimates of the hardest-hit industries.

Chart 4 illustrates the industry share of small businesses in each of the six hardest-hit industries affected by social distancing policies. Overall small businesses in retail trade, accommodation and food services, and transportation and warehousing account for the largest portions (89 percent) of hardest-hit industries in the Southeast. Chart 5 further shows the share of employment for each of these hardest-hit industries. Accommodation and food services, retail trade, and transportation and warehousing represent 85 percent of jobs in hardest-hit industries.

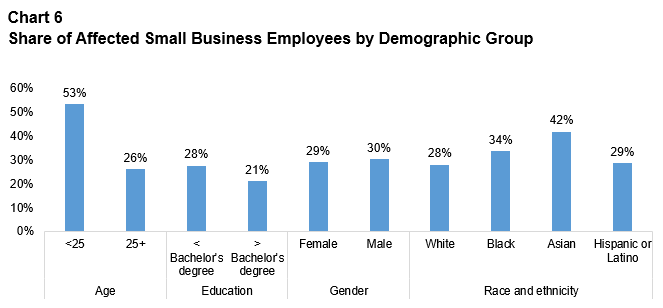

Many employees of these small businesses have experienced layoffs, furloughs, and job disruptions. As a share of the total working population, chart 6 shows that people of color, younger, and less educated workers have a greater likelihood of being employed in the hardest-hit industries compared to their counterparts, and therefore they may be more susceptible to economic fallout from COVID-19 in the Southeast.

Source: 2017 Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics10

While this analysis has shown the industries and employees most likely negatively affected by COVID-19, some of our interviewees indicated there are industries that remain relatively insulated. They even highlighted subsectors that experienced spikes in demand for goods and services, including information technology and manufacturing. Some firms have pivoted their production models, such as distilleries now producing hand sanitizers, and some advanced manufacturing firms are now 3-D printing personal protective equipment.

Conclusion

Small businesses are the engine of our economy and critical job creators in our communities. In the Southeast, these businesses account for well over 97 percent of all firms and are responsible for almost 44 percent of all jobs. Given the rippling economic implications of COVID-19, over 23 percent of these small businesses fall within the hardest-hit industries for each state in the Southeast. These businesses will likely need support to restart as states reopen. The insights from interviewees highlight both the severity and saliency of bolstering small businesses to help jump-start an inclusive recovery. While the COVID crisis is certainly unprecedented, the opportunity to create deliberate and intentional recovery strategies is well within our collective reach.

By Janelle Williams, senior CED adviser, and Mary Hirt, CED engagement analyst II

_______________________________________

1 See https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/21060437/Small-Business-GDP-1998-2014.pdf.

2 The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's District includes all of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, and parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. For the purposes of this article, "Southeast" will be used interchangeably with the Atlanta Fed's District and refer to the entirety of the six states.

3 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Business Employment Dynamics Table 7. Survival of private sector establishments by opening year."

4 Author's calculations based on the 2016 Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs.

5 Ibid.

6 Chuck Collins, Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Josh Hoxie, and Emanuel Nieves. (2017). "The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide Is Hollowing out America's Middle Class." Prosperity Now and Institute for Policy Studies. https://ips-dc.org/report-the-road-to-zero-wealth/

7 Stoll, Michael A., Steven Raphael, and Harry J. Holzer. (2001). "Why Are Black Employers More Likely than White Employers to Hire Blacks?" Institute for Research on Poverty, Discussion Paper no. 1236-01. https://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/dps/pdfs/dp123601.pdf

8 See Alexander W. Bartik, et al. (2020). "How Are Small Businesses Adjusting to COVID-19? Early Evidence from a Survey." National Bureau of Economic Research working paper 26989.

9 These industries include retail trade; arts, entertainment, and recreation; accommodation and food services; and construction. The level of physical proximity is estimated based on the occupation's tasks in close physical proximity to other people from O*NET (see more details and analysis by Wardrip and Tranfaglia at www.philadelphiafed.org/covid-19/covid-19-equity-in-recovery/which-workers-will-be-most-impacted).

10 Authors' estimations are based on "hardest-hit" sectors of nonessential businesses closures for the Southeast. The graph represents the share of affected hardest-hit small business employees out of all small business employees within that demographic characteristic.

Example: 53 percent of workers under 25 years old are in hardest-hit sectors.