Health status is a major determinant of a person’s ability to participate in the labor force and earn income. Recent research from the Atlanta Fed provides new insights on the role of health in creating disparities in lifetime earnings.

A working paper published in January finds that the primary reason adverse health increases income inequality is because sick and disabled people are more likely to quit working and apply for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), the government program that provides cash benefits to those who are unable to work because of a medical condition.

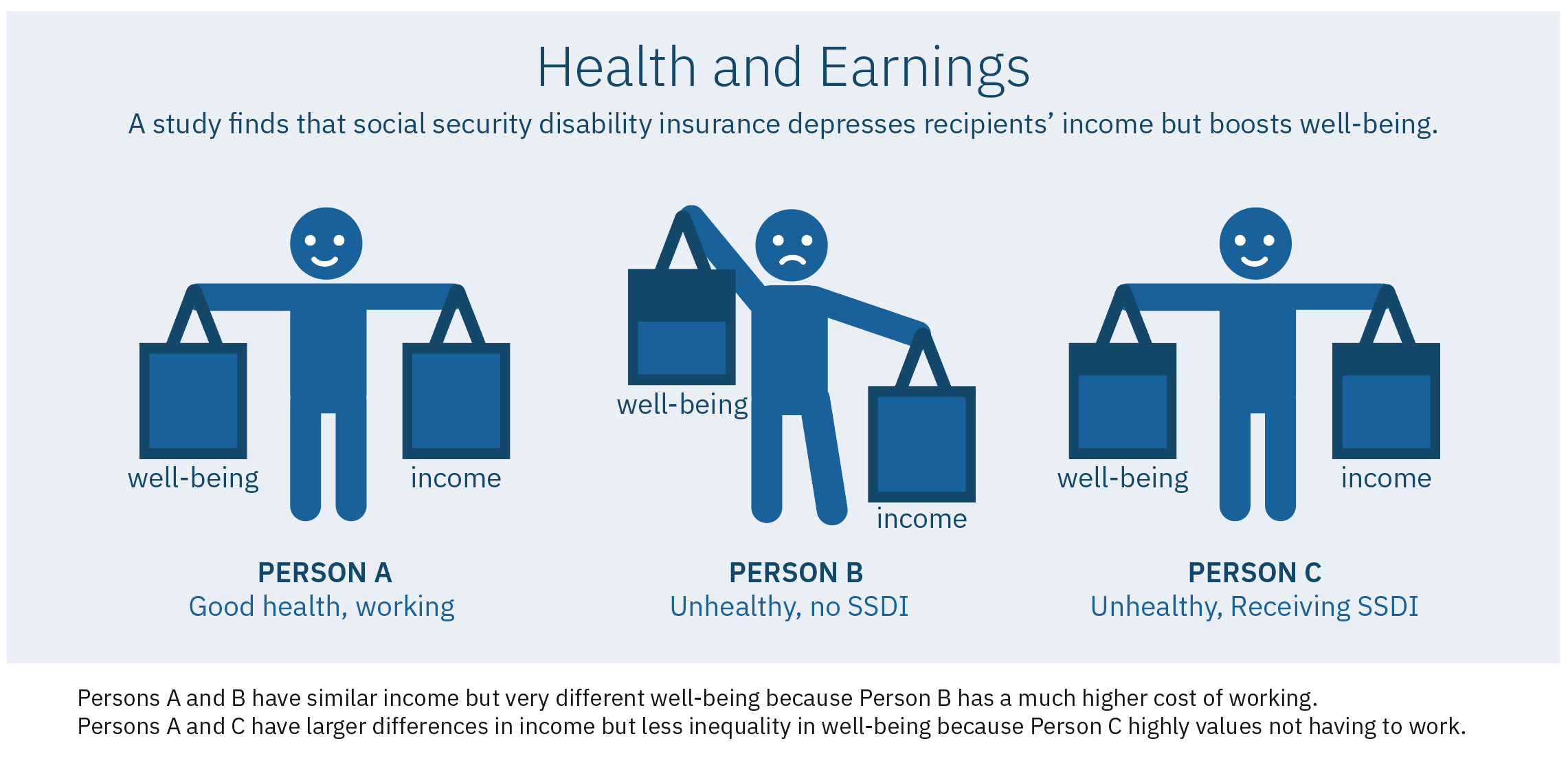

However, the research also found that SSDI facilitates a worthwhile trade-off. While the safety-net program contributes to income inequality by reducing a recipient’s earnings during their lifetime—a major drawback—it also improves the overall well-being of people who are in poor health.

“Income isn’t everything”

“When thinking about how to evaluate a program like SSDI, income isn’t everything,” said Karen Kopecky, a Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta research economist and adviser. “What you really want to think about is welfare and the fact that people might be willing to live with lower earnings if it means that they can be happier in other ways.”

The Atlanta Fed’s Karen Kopecky. Photo by David Fine

Kopecky wrote the working paper on health and earnings inequality with two other researchers, Roozbeh Hosseini of the University of Georgia and Kai Zhao of the University of Connecticut. They explain that bad health can affect individuals’ work life and financial standing in various ways. Illness can increase the risk of death, raise out-of-pocket medical expenses, boost unfavorable physical and mental effects from working, hurt labor productivity and wages, and enhance the likelihood of obtaining benefits under SSDI. Of these factors, the possibility of obtaining disability benefits has the potential to have the biggest negative impact on earnings disparity, the researchers’ analysis shows.

To determine the effect of health on earnings, the researchers used a measure of health called the frailty index, which focuses on the number and nature of illnesses a person has, and examined data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which includes survey questions on specific medical conditions and daily living activities. (Read more about the frailty index here.)

The findings showed that health shocks have a marked effect on pay, with the addition of even one medical ailment lowering earnings by 20 percent on average among the general population, including both employed people and those out of the labor force. However, the study indicates that the earnings reduction from one additional illness is much lower—4 percent—for people who work. Not surprisingly, people in bad health endured a deeper drop in earnings than those in good health. These results are explained by the fact that people who are less healthy tend to leave the workforce rather than work fewer hours or get paid lower wages, the paper stated. “People in bad health don’t work, and because they don’t work, their earnings are basically zero,” Kopecky said.

The study also shows the effects of adverse health on earnings across education groups, with the more highly educated faring better. For example, in the general population, one additional health ailment decreases the earnings of high school dropouts and high school graduates by 23 percent and 21 percent, respectively. That compares with an income drop of 9 percent for college graduates. Earnings reductions were smaller among working adults, regardless of their educational level, the results indicated.

Social security disability insurance is a prime driver of the lifetime earnings disparity that results from illness, the researchers assert. The SSDI program began in 1956 and is paid for with payroll tax contributions of U.S. workers and employers.

Because of strict rules surrounding the SSDI program—applicants must have a significant medical impairment, have been out of work or had very low earnings for at least five months before payments can be received, and can be kicked off the program if income exceeds a certain level—most recipients do not work.

Testing a hypothetical

The researchers also sought to learn what eliminating the U.S. disability insurance program would mean, and they conducted experiments to determine the effects of such a move. The results demonstrated that taking away SSDI decreases inequality in earnings, because people receiving those benefits are less likely to leave the labor force if the insurance isn’t available.

But the study also points to another important, and sobering, finding: removing SSDI reduces welfare—which basically means happiness and well-being—among the general population. The decrease in welfare occurs, the researchers explain, because less educated people lose the protection against the risk of bad health that SSDI provides. College graduates, who tend to use SSDI less, benefit from removing the program because the taxes they pay to fund it decline. However, overall, the loss in welfare of the less educated exceeds the welfare benefits of college graduates, the analysis found.

The researchers conducted additional experiments to determine the effects of expanding and reducing SSDI benefits. Those analyses indicated that raising payments would likely help high school dropouts and high school graduates more than it hurts people who are college educated. Because all people face health risks and disability can strike at any point in a person’s life, the government disability program is meaningful and should be expanded, the researchers conclude.

Kopecky noted that working can be difficult and painful for people who are disabled or medically impaired, and she pointed out that people who are in bad health are not as productive while employed. SSDI recipients are willing to sacrifice income to be spared the pain of working, she said.

“SSDI could be viewed as a bad program because it contributes to income inequality,” Kopecky explained. “But from a welfare perspective, it’s a good program because the people who would have low income and are on SSDI are much better off with the program than without it.”