The preparation for Federal Open Market Committee meetings never stops.

The moment a session ends and Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic walks out of the headquarters of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors—or, these days, when he shuts off his computer’s video feed—he and a cast of dozens begin compiling material to inform his views for the next meeting of the committee, usually referred to as the FOMC.

But 2021 is a bit different for Bostic. That’s not only because the two-day meetings where the committee sets the nation’s monetary policy are virtual but also because Bostic is a voting member this year.

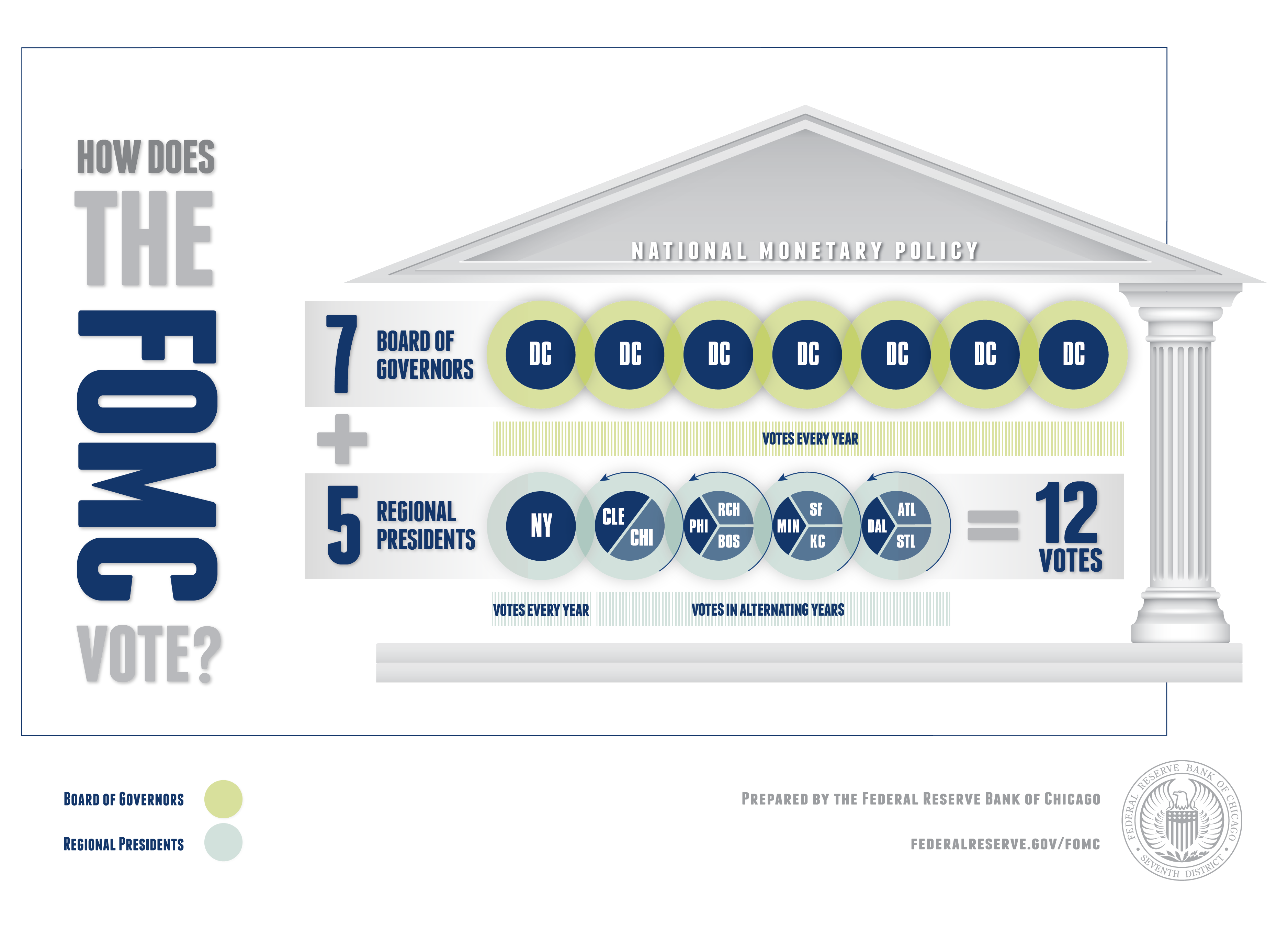

The Atlanta Fed president rotates with the presidents of the Dallas and St. Louis Reserve Banks, which means Bostic votes every three years. All Federal Reserve governors vote, along with five bank presidents—the New York Fed’s leader and four others in rotation (see the infographic).

Voting or not, for Bostic the preparation and mechanics of FOMC meetings are the same. “We still have the same opportunities to speak and participate,” Bostic said before the most recent meeting on March 16 and 17. “The insights of every committee member help inform the collective view about the appropriate path of policy.”

Meetings carefully planned but also free ranging

Although meticulously planned, the committee’s meetings vary in length from six-and-a-half to roughly 10 hours on the first day, depending on economic circumstances and how much Fed action needs to be dissected and discussed. The second-day sessions are shorter because the FOMC statement must be approved and issued publicly by 2 p.m. eastern time, and Fed chair Jerome Powell holds a news conference at 2:30 p.m.

Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic. Photo by David Fine

While the six governors—a full complement is seven, but as of March one seat on the Board sat open—and the 12 presidents are the actual policymakers, they are not alone in FOMC sessions. Committee members are joined by five dozen or so staff, including economists and regulatory experts.

In fact, after administrative procedures such as authorizing open market transactions that serve to keep the federal funds rate in the prescribed range, a team of Board economists discusses economic and financial conditions. At certain meetings, staff experts give in-depth reports on a particular issue.

After that, committee members make presentations.

First comes the “economy round,” in Fed lexicon. In this phase of a meeting, each FOMC member airs views on the macroeconomy, often including current conditions and the outlook.

“It can cover anything they want—labor markets, inflation, international markets, banking, financial markets, inequality,” Bostic explained. “It’s really the member’s decision as to what they want to emphasize.”

Bostic likes to include in his comments on-the-ground insights from business operators. The Reserve Bank’s Regional Economic Information Network staff continually collect reports from firms across a range of industries. The Atlanta Fed was among the first regional Reserve Banks to formalize a District-level intelligence-gathering operation and, with it, the processes to analyze and synthesize the information. Ultimately, that input adds texture to macroeconomic data to complete the picture for Bostic.

For example, in recent weeks many business contacts have reported trouble filling certain jobs, despite high unemployment. That phenomenon has been less apparent in the aggregate labor market data.

This sort of input is particularly useful amid the turmoil caused by the pandemic, Bostic noted. Conditions are apt to change so quickly that anecdotal reports lend important nuance to official data showing what happened a month or more in the past.

No time limits

Although each committee member’s presentation differs in length—there is no time limit—Bostic tries to keep his remarks to three to five minutes. Like Powell’s two immediate predecessors, Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, the chair usually opts to speak only after hearing all the other committee members, Bostic said.

Members generally ask each other questions and share comments. Minutes published three weeks after each meeting summarize the discussions. The minutes, which took their present form in 1993, are meant to inform the public about the range of committee members’ views on the appropriate policy stance and the economic outlook.

At the January 26–27 session, for instance, most participants said they expected a set of forces—including fiscal relief passed by Congress in December and March and anticipated progress in vaccinations—to produce “a sizable boost in economic activity.”

At the same time, participants noted that economic activity and employment remained well short of conditions that suggest the economy is at maximum employment, which is one of the Fed’s two primary objectives (the other being price stability).

After the “economy round” comes the “policy round,” which is when committee members deliberate the current stance of monetary policy and actions to be taken at that meeting. They also offer suggestions on the text of the statement that will be issued after the meeting.

Voting to approve the policy action and statement is the final action at each FOMC meeting. After the statement is released and Powell addresses the press, Bostic moves on to the next cycle of briefings with economists and analysts, meetings with businesspeople, and gathering other research meant to paint the most comprehensive picture possible of the nation’s ever-changing economy. After all, the preparation never stops.