Photo by David Fine

Editor's note: This is part one of a series exploring transit-oriented development in the Southeast.

A folding placard near the Atlanta transit system's Avondale Station makes a humble promise: "New Things Coming."

The new things are under construction—470 apartments, 34 condominiums, and street-level space for shops and restaurants. Despite the unassuming sign, this is not just another mixed-use development amid hundreds of similar projects across metropolitan Atlanta.

This transit-oriented development, or TOD, is being birthed by the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) itself, in partnership with private builders. It is one of three MARTA TODs under construction, with four others in the planning stages. MARTA wants its TODs to boost revenue and ridership. In addition, each project with a residential component includes a goal of making 20 percent of the units affordable for low-income residents.

That goal is crucial. Like metropolitan areas across the nation, Atlanta faces a severe shortage of housing that is affordable to low-income residents. Estimates put the national shortage of available and affordable rental apartments or houses at about 7 million, and TODs are becoming a more common way to increase the stock of affordable housing. However, the shortage is acute enough that TODs are but one of many strategies needed to confront it, according to researchers including Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic.

TODs can be an important part of the affordable-housing strategy of a city or region, in part because they typically allow for dense concentrations of housing, according to Bostic, a housing economist who collaborated with colleague Marlon Boarnet and several graduate students at the University of Southern California to study the challenges involved in using TODs to decrease driving and add affordable housing in the Los Angeles area. Density is critical to create affordable housing while achieving other goals typically embedded in TOD plans, Bostic noted.

"Allowable development densities are often higher near transit stations," he said, "meaning one gets more unit bang for the buck by developing in this way."

Affordable housing a bigger part of TOD strategies

When MARTA began formulating its TOD policies more than 10 years ago, few transit agencies considered affordable housing requirements, recalls Amanda Rhein, the agency's senior director of TOD and real estate. Affordable housing receives more attention now, as the shortage of such housing has become more acute and federal and local transit agencies have taken a more comprehensive approach in tying funding criteria to combined transportation and housing strategies.

This approach makes sense for numerous reasons, according to researchers. The biggest: Providing affordable housing near transit, especially for lower-income people who are more likely to need public transportation, bolsters regional economies by improving access to jobs and helping employers grapple with labor shortages.

Including affordable housing in TODs may also reduce household vehicle miles traveled for low-income families who otherwise would live outside TODs. And it may curtail gentrification and displacement in communities where transit stops are established. In short, locating affordable housing near transit produces "meaningful benefits" for communities at large, Bostic said.

But it's tricky

Some of the nation's most acute shortages of affordable housing are in booming southeastern metro areas such as Orlando and Miami, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. The region's biggest metro areas also rank low in terms of transit access to employment and economic mobility (see the chart). Economic mobility refers to the chances for low-income people to move up the income scale.

Physical and economic mobility are related, as the ability to reach a job in a reasonable time significantly affects a person's chances to work productively, economists such as Stanford University's Raj Chetty have found. This "spatial mismatch" of jobs and affordable housing has drawn increasing attention from researchers over the past decade. To find housing, lower-income families often must venture far from job centers and public transportation. As a result, they face longer commutes and higher transportation costs.

Low- and moderate-income households on average spend 60 percent of their income on housing and transportation, a disproportionately high figure that contributes to increasing income inequality and wealth disparities in the United States, according to 2017 research by Ann Carpenter of the Atlanta Fed's Community and Economic Development department and two coauthors.

TOD strategies increasingly target those socioeconomic challenges. "If we're going to begin to provide a ladder of opportunity," said MARTA's Rhein, "transit is going to be an important part of that solution."

It won't be easy. One of the core problems in addressing the affordable housing shortage in TODs or any setting is that market forces tend to exacerbate the problem—hence, the role of public policy.

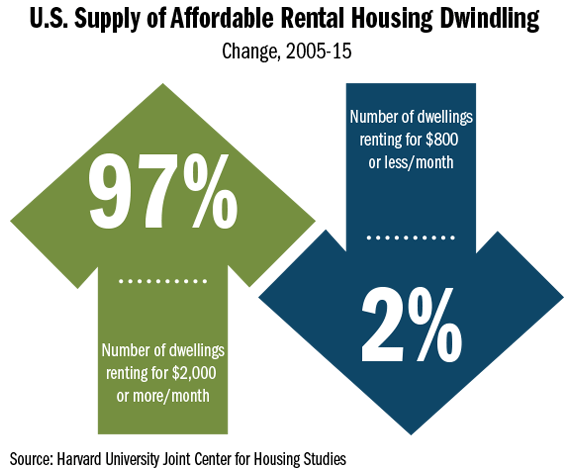

Climbing construction and land costs make it difficult for private developers to profitably build affordable units, one reason behind the dwindling supply of affordable housing. According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, from 2005 to 2015, the number of houses and apartments renting for $2,000 or more per month nearly doubled while the number renting for less than $800 declined (see the chart).

Like the country as a whole, the Southeast appears to be losing low-cost rental housing. Carpenter, Dan Immergluck of Georgia State University, and Abram Lueders of the Downtown Memphis Commission examined rental housing supplies in Atlanta, Birmingham, Jacksonville, Memphis, Miami, Nashville, Orlando, and Tampa. Their 2016 paper found that between 2006 and 2014, the number of rental units priced at $750 a month or less decreased in all eight cities by hundreds—and in some cases, thousands—each year.

Meanwhile, incomes, especially among lower-income earners who tend to be renters, have risen only gradually in recent decades. Tepid income growth and rising rents have conspired to erode housing affordability in virtually every metro area in the country over the past 25 years, according to Bostic and his collaborators.

TODs might help. But in the pursuit to add affordable housing, TODs offer both unusual opportunities and challenges. In TODs, as elsewhere, developing affordable housing that remains affordable for decades is a complex undertaking. For one, building near transit stations can be particularly expensive because land values are usually high and meeting federal standards to qualify for affordable housing subsidies can add to construction costs.

What's more, rail stations tend to increase surrounding property values, putting upward pressure on home prices, Bostic and his colleagues point out. Consequently, "there is some probability that units that are initially affordable will not be in the future," they wrote.

Photo by David Fine

In some cases, transit stations have led to gentrification and the displacement of lower-income residents, Bostic and his team found. Seva Rodnyansky, a USC doctoral student working with Bostic and Boarnet, examined microdata on household moves out of rail station areas in Los Angeles and found evidence that the opening of new rail transit is associated with an increase in moves out of the neighborhood, a conclusion also reached by other researchers.

To help keep residences in TODs accessible for those who stand to benefit most, affordable housing incentives have become common. MARTA requires that 20 percent of residences in its TODs be affordable for tenants whose household incomes don't exceed 80 percent of the area median.

But nationwide, those incentives usually expire after a certain term, and so what is affordable housing at first may not remain so, Carpenter said. MARTA's affordable housing requirement is 30 years, according to Stephany Fisher, the agency's acting senior director of communications. But once an initial affordability period expires—generally after 10 to 15 years—the lessee then must make "a good faith effort to identify other sources of subsidy to continue the affordability period through the end of 30 years," Fisher noted.

Environmental and affordable housing goals sometimes conflict

Balancing the goals of increasing ridership, reducing car trips and thus air pollution, and adding affordable housing is anything but straightforward.

In fact, the twin goals of creating affordable housing while reducing cars' greenhouse gas emissions can be in conflict, as Bostic's research explores (see the chart). Density of development is a crucial bridge between the two objectives. Bostic and his fellow researchers found that TODs including more housing units, combined with a small percentage set aside for affordable housing, produce greater benefits in reduced driving and affordable housing than would a higher affordable housing percentage and less density. At a certain density, they write, "the tradeoff between environmental and housing affordability interests evaporates."

But even striking the right balance is no panacea. The researchers warn that higher density can create its own problems. It can increase auto traffic congestion (not everyone will exclusively use transit), hurt public perceptions of the development, and create political backlash.

The papers by Bostic, Boarnet, and the graduate students include a set of recommendations for policy makers.

- Increase subsidies for affordable rental units near transit, both in and outside TODs. Planners might need to get creative in identifying funding sources to spur high-density development, such as tapping the Low Income Housing Tax Credit or awarding developers bonuses tied to density. Planners should also anticipate political pushback.

- Try to reduce the number of affordable units that opt out of subsidies. Planners can work toward this goal by making project-based Section 8 programs more attractive for developers. (Under project-based Section 8 programs, private landlords receive public subsidies to build or renovate units that cap the rents landlords can charge.) Local officials could aim to lower bureaucratic hurdles in these programs by, for example, requiring just one rather than multiple annual physical inspections of a property.

- Expand the stock of affordable units generally, with a focus on TODs and areas near transit.

Building affordable housing in TODs complicated but doable

Though Bostic and his coauthors' research focused on Los Angeles, he believes the basic findings are relevant elsewhere in two main ways. First, the research captures a reality—increasing traffic congestion and miles driven and dwindling affordable housing—with which many metro areas struggle. Second, the benefits flowing from community investments in density and housing affordability are not limited to TODs.

Research suggests that TODs are not a magical solution to an affordable housing shortage so severe that some describe it as a crisis. Indeed, federal funding for rent subsidies has steadily declined in recent years and could decline even more sharply. But TODs are one tool. Although the concept of the TOD took root in the early 1990s, employing them as a means of adding low-income housing is still a relatively new and largely unproven concept.

Still, as complicated as it is to build durably affordable housing in TODs, communities can do it, Bostic said. "But they have to decide that it is a priority, and then make the necessary institutional and process changes to increase the chances that affordable housing gets built."