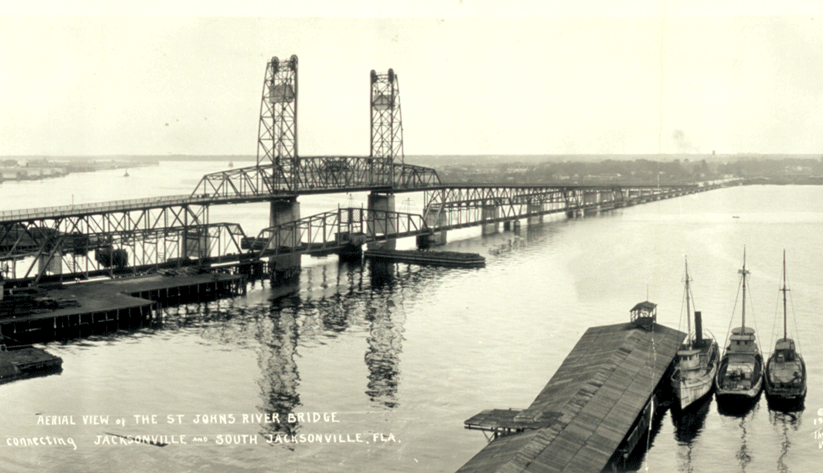

A view of the St. Johns River Bridge, later known as the Acosta Bridge, in 1927. Opened in 1921, this bridge came down in the 1990s, replaced by an entirely new Acosta Bridge. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress photographic archives

A view of the St. Johns River Bridge, later known as the Acosta Bridge, in 1927. Opened in 1921, this bridge came down in the 1990s, replaced by an entirely new Acosta Bridge. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress photographic archives

Editor's note: This is the fourth story in a series exploring the economic histories of some of the largest metropolitan areas in the Southeast.

It can be easy to forget how comparatively new modern Florida is. After all, the Sunshine State's population did not exceed neighboring Alabama's until the 1950s. Today, Florida is home to more than 20 million people, making it the third-largest state.

But when Florida was mostly a swampy curiosity to the rest of America, Jacksonville was the state's principal city. Before Henry Flagler's crews laid rails down the east coast, Jacksonville—not Miami, Orlando, or the Keys—was the destination of choice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for the well-heeled seeking refuge from northern winters. Jacksonville's population would double, even triple during the winter, according to the Jacksonville Historical Society. In 1918, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta opened its Jacksonville Branch, helping to solidify the river city's status as a regional financial hub. The city even became a center of the silent film industry in the early 20th century.

The arrival of tourists and moviemakers was part of a revival following what may still be the most epochal event in Jacksonville's history, economic or otherwise. The Great Fire of 1901 destroyed some 90 percent of the city and left more than a third of the population homeless. Rebuilding proved an economic stimulus, said James Crooks, a historian and professor emeritus at the University of North Florida in Jacksonville.

A changing composition

Soon enough, though, the studios and tourists largely moved on. The 30 film studios moved to California by the 1920s. Meanwhile, tourists began traveling farther south along the new railroads and eventually Dixie Highway, later U.S. Highway 1. Shipbuilding, sawmills, and paper would soon become economic staples in Jacksonville, drawing on the rich pine and oak forests of northern Florida and southern Georgia.

Those industries have faded with time. However, economic activity spurred by the buildup to World War II has proven more lasting. Local shipyards produced more than 100 vessels starting in 1942, including Liberty Ships, Victory Ships, tankers, minesweepers, and PT boats. More importantly, two naval bases opened in the early 1940s, Naval Air Station Jacksonville and Naval Station Mayport.

Those military installations drew thousands to Jacksonville and still employ more than 20,000 people. With families, military personnel, their families, and other workers, the naval bases' combined population approaches 100,000 people, according to data from the Department of Defense. Jacksonville has one of the bigger Navy presences among U.S. metropolitan areas.

Nevertheless, the Jacksonville bases are home to fewer large ships than in the past. And the portion of local economic activity attributable to the military was 2.7 percent in 2015, the most recent figure available, roughly half the share in 2001, according to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. The military accounts for a much bigger proportion of local gross domestic product in Navy hubs such as Honolulu, Norfolk-Virginia Beach, and San Diego.

Something in the air

A handful of paper mills and chemical plants were quite apparent—to the eyes as well as the nose—for decades. Air pollution from those plants, especially odors, were a serious local problem before the 1990s. Along with challenges such as racial strife and poor public schools, air and water pollution tarnished Jacksonville's image and hindered business recruitment for years, according to Crooks. The odors tainted Jacksonville's reputation during the 1960s and were a disincentive to business recruitment, he noted.

A couple of mills remain but the smell is gone. And though a local railroad executive once famously described the offending odors as “the smell of money,” manufacturing never made up a large share of Jacksonville's total employment, according to various histories.

Still, in 1990, manufacturing employment was nearly on par with the share of work in financial activities, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data. Yet the composition of local employment has changed significantly in the past quarter century. Finance, health care, and education have emerged as economic linchpins.

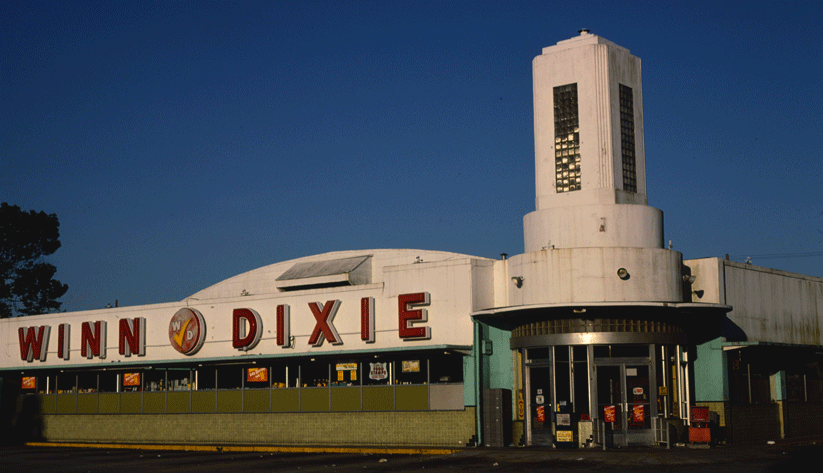

Jacksonville as seen from the St. Johns River Bridge in 1921. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress photographic archives

Financial sector employment moves to center stage

Since 1990, Jacksonville metro area manufacturing employment has declined about 15 percent, about half the decline nationally. In the same period, the number of jobs in what the BLS defines as financial activities has soared 70 percent, to roughly 69,000.

That growth more than doubles the rate of growth in finance employment nationally. Finance, including a major presence in the insurance business, now accounts for roughly 10 percent of metro Jacksonville's nonfarm employment, a share nearly double the national one and more than the share in the New York City metro area. Finance employment in Jacksonville has actually more than made up the ground lost during the Great Recession.

Jacksonville has benefited as some financial institutions have moved jobs there from expensive offices in New York City. High-end office space in New York City on average rents for about three times what it does in Jacksonville, according to CoStar Property, a real estate data firm. And banks pay Jacksonville employees about 30 percent less on average than they'd pay similar workers in New York, according to Jacksonville economic development officials. Deutsche Bank is a notable exemplar of financial “nearshoring.” The big German investment bank employs 2,250 at its Jacksonville operation, up from fewer than 100 in 2008, according to the Jacksonville's chamber of commerce and Bloomberg.com.

Jacksonville's banks, insurance companies, and investment firms tend to be big. Among a list of Jacksonville's largest private-sector employers, 40 percent of the 62 firms with 500 or more workers are in finance or insurance, according to JaxUSA, the economic development arm of the chamber of commerce.

The insurance industry's relationship with Jacksonville is not a new one. In 1953, state law began allowing tax benefits to out-of-state firms. By the end of the 1950s, Jacksonville counted 17 locally based insurance companies and five regional home offices, according to Crooks. On the banking side, Jacksonville was home to three large institutions, including Barnett Bank. Barnett was founded as the Bank of Jacksonville in 1877 and was the largest commercial bank based in Florida when it was acquired by NationsBank—later Bank of America—in 1997.

Jacksonville's economy has expanded nicely over the past 30 years. Metro Jacksonville's total nonfarm employment, in fact, has grown 69 percent since 1990, same as Atlanta's, and better than Miami's and Tampa's job growth, according to the BLS. Only Orlando has done better among the Sunshine State's biggest metros. Not bad for a city that was once a haven for snowbirds.