Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy Conference

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

March 22, 2019

- Atlanta Fed president and CEO Raphael Bostic speaks at the San Francisco Fed's Macroeconomics and Monetary Policy Conference about the Federal Open Market Committee's recent decisions in managing the latter stages of policy normalization.

- Bostic says monetary policy from here on will be conducted using a "floor system," in which the FOMC controls rates by way of administered interest rates rather than by manipulating the supply of scarce reserves. Put directly, the FOMC will not be returning to the pre-crisis operating framework.

- Bostic explains that the Fed's balance sheet will be large relative to the pre-crisis norm, independent of the decision to implement monetary policy in a framework with ample reserves.

- Bostic says that the FOMC continues to view the federal funds rate target as the primary tool to adjust the stance of monetary policy.

- Bostic warns against misinterpretation of what the FOMC means by patience. He does not view this patient approach as constraining the Committee's options and is open to all possibilities as the FOMC aims to support sustained economic expansion, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee's symmetric 2 percent objective.

Thank you, Mary, for the kind introduction. It's always good to be back in the Bay Area. I went to graduate school just down the road, as Mary noted. I spent a lot of time immersed in my studies and a little bit of time enjoying myself. But we'll leave that discussion for another day.

Thank you all for being here and for the important work you're doing. This research is especially timely, as we at the Federal Reserve are undertaking a review of our strategic framework for monetary policy. We are examining our policy strategy, tools, and communications practices. As part of the strategic review, the Federal Reserve System is sponsoring a research conference in Chicago in June. I suspect some of you may be there.

As I'll discuss in some detail, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC, or the Committee) is entering the later stages of normalizing the extraordinary tools it deployed in the wake of the financial crisis. So this seems an important moment to take stock of issues raised by the remarkable experiences of the past decade.

Just over 10 years ago, the Committee lowered the federal funds rate to near zero, the effective lower bound. As the Committee could move rates no lower, it turned to two novel tools to promote the recovery from the Great Recession. One was large-scale purchases of longer-term securities, which became known as quantitative easing, or QE.

This policy substantially expanded the Federal Reserve's balance sheet, from about 6 percent of gross domestic product in 2006 to nearly 25 percent of GDP in 2014. The other novel tool was forward guidance, or communicating about the future path of interest rates.

From the beginning, the Committee viewed these moves as extraordinary measures to be unwound, or "normalized," when appropriate. Normalization of the balance sheet began 17 months ago. In January, and earlier this week, the FOMC announced important decisions regarding its approach to managing the latter stages of this process.To be specific, in January the Committee announced that it had decided to continue with an operating framework in which bank reserves are "ample." That decision was followed this week by the decision to stabilize the size of the balance sheet, at least for a while, starting in October. In short, monetary policy from here on will be conducted using what is commonly known as a "floor system," in which the Committee controls rates by way of administered interest rates rather than by manipulating the supply of scarce reserves.

Put directly, the FOMC will not be returning to the pre-crisis operating framework. Because of that, I think it's important to be crystal clear about the rationale for this decision, at least as I see it. To that end, I want to make three basic points in my remarks today.

First, the balance sheet is destined to be large relative to the pre-crisis norm, independent of the decision to implement monetary policy in a framework with ample reserves. In fact, I will argue that the ultimate driver of the size of the Fed's balance sheet will be factors other than the FOMC's operating framework.

My second point is that, regarding the transmission of policy actions to short-term interest rates, there has so far been no discernible distinction between the old operating framework and the new operating framework. As a practical matter, all evidence points to little difference in the effectiveness of monetary policy when the central bank operates in a system with ample reserves.

Finally, I want to lay out the reasons that I supported the decision to maintain an ample-reserve framework going forward.

As always, I'm speaking strictly for myself, and not for my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee or at the Atlanta Fed.

Big ain't what it used to be

On to my first point, then, which is to caution that the discussion about the FOMC's operating framework should not be conflated with a debate about the size of the Fed's balance sheet.

When it comes to the size of the Federal Reserve's balance sheet, an often overlooked factor is the organic growth that results from increases in the public's demand for currency. In fact, the Fed's balance sheet was steadily growing over time before the crisis as a passive response to the public demand for cash.

During the crisis and post-crisis recovery, currency demand accelerated. From the end of July 2008 to the end of 2018, the amount of currency nearly doubled in nominal terms. Thus, even in the unrealistic event that currency demand stabilizes and the FOMC shrinks reserves to a minimal amount, the balance sheet would still be about twice as big today as it was at the end of 2007 when the Great Recession was beginning. I say this scenario is unrealistic because currency demand does grow over time. But it is also unrealistic because it is highly unlikely that reserves can be maintained at pre-crisis levels. This is so even if the FOMC were to return to its pre-crisis framework.

Let me explore that thought in a little more detail. The pre-crisis framework worked by engineering enough scarcity in the supply of reserves to ensure that small changes in quantity would impact the price—the federal funds rate. But as we all know, scarcity is not an absolute concept. It depends on the level of demand. In the pre-crisis era, the demand for reserves by the banking system was relatively small. That meant that federal funds rate control could be accomplished with changes in the supply of reserves that were correspondingly small.

Things have changed. Lorie Logan, the deputy manager of the System Open Market Account, gave a nice discussion of the central issues during a panel discussion sponsored by the Hoover Institution last May. The short version is this: changes in banking regulations, the business models of financial institutions, and Treasury management of their accounts held with the Federal Reserve imply that the demand for reserves today is likely to be much larger (and perhaps more volatile) than it was in the pre-crisis world.

One key implication of an increase in the structural demand for reserves is that reserve scarcity will likely be associated with a balance sheet that is relatively large. Estimates of average reserve demand vary, but something around $1 trillion does not seem unreasonable to me. And it likely will be appropriate to maintain a buffer on top of estimated average demand to accommodate temporary fluctuations in demand. That's a couple of orders of magnitude larger than the pre-crisis, pre-Dodd-Frank norm. When it comes to reserves in the banking system, a trillion is the new 45 billion.

What is more, the FOMC has made clear its intentions to "in the longer run, hold no more securities than necessary to implement monetary policy efficiently and effectively." The precise implication of this, quantitatively, is yet to be determined. But as a practical matter, it is not clear that the choice of an ample- versus scarce-reserve framework will have a material impact on the size of the balance sheet.

Recent history under a floor system

Thus far, I have argued that the desire for a smaller Fed balance sheet does not provide a very convincing case for returning to the pre-crisis operating framework. What would be a convincing case? I know I would be very skeptical about adopting a floor system if it appeared that central bank control over bank borrowing and lending rates had deteriorated in the period since 2009, when we have actually had a floor system in place. Fortunately, I do not believe that to be the case.

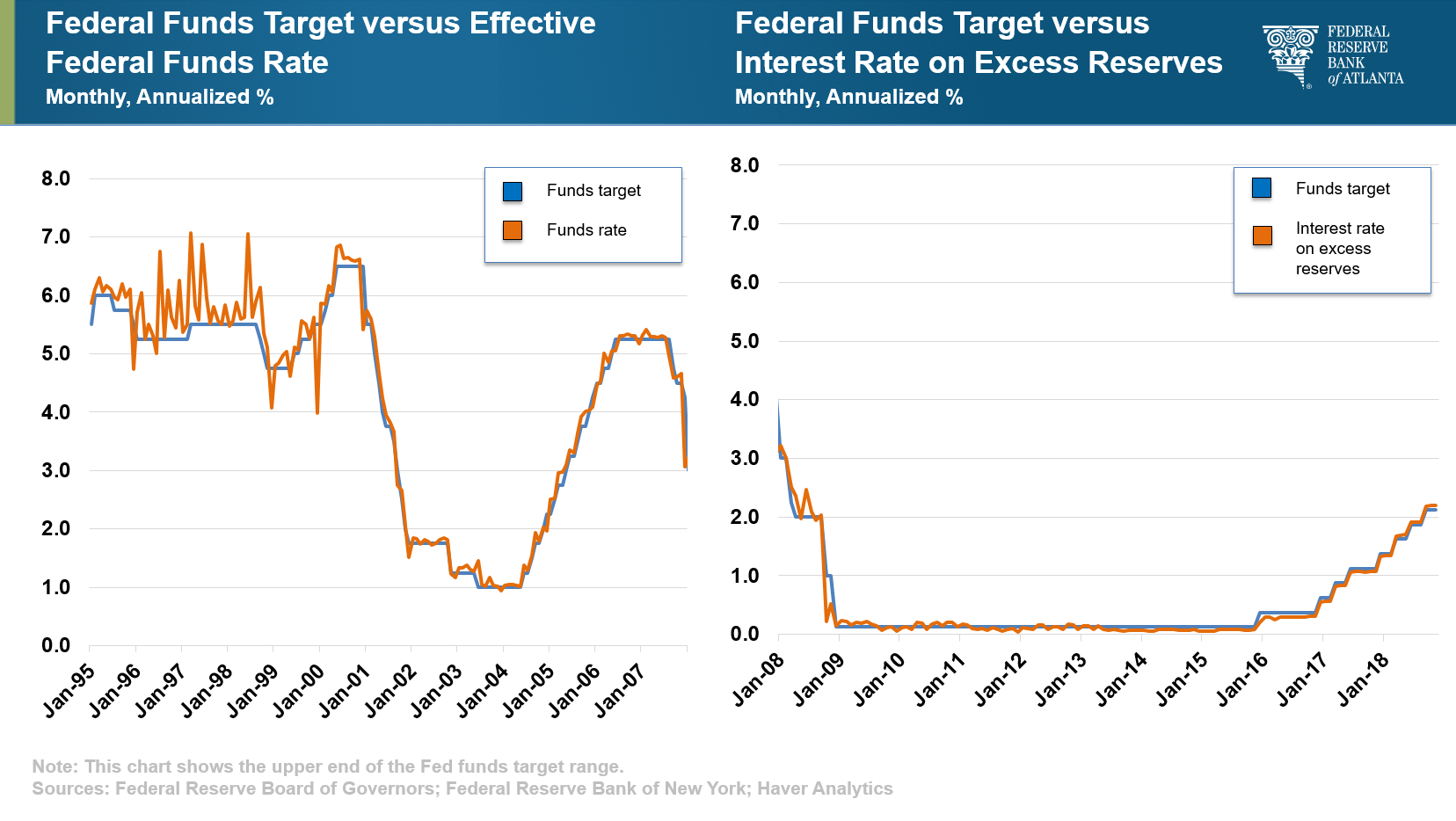

The charts I am showing here illustrate the relationship between the federal funds rate target and the actual market value of the funds rate for the pre-crisis period from 1995 through December 2007, and then the upper end of the federal funds rate target range juxtaposed with the Interest-Rate-on-Excess-Reserves for the abundant-reserve period from December 2008 through November 2018.

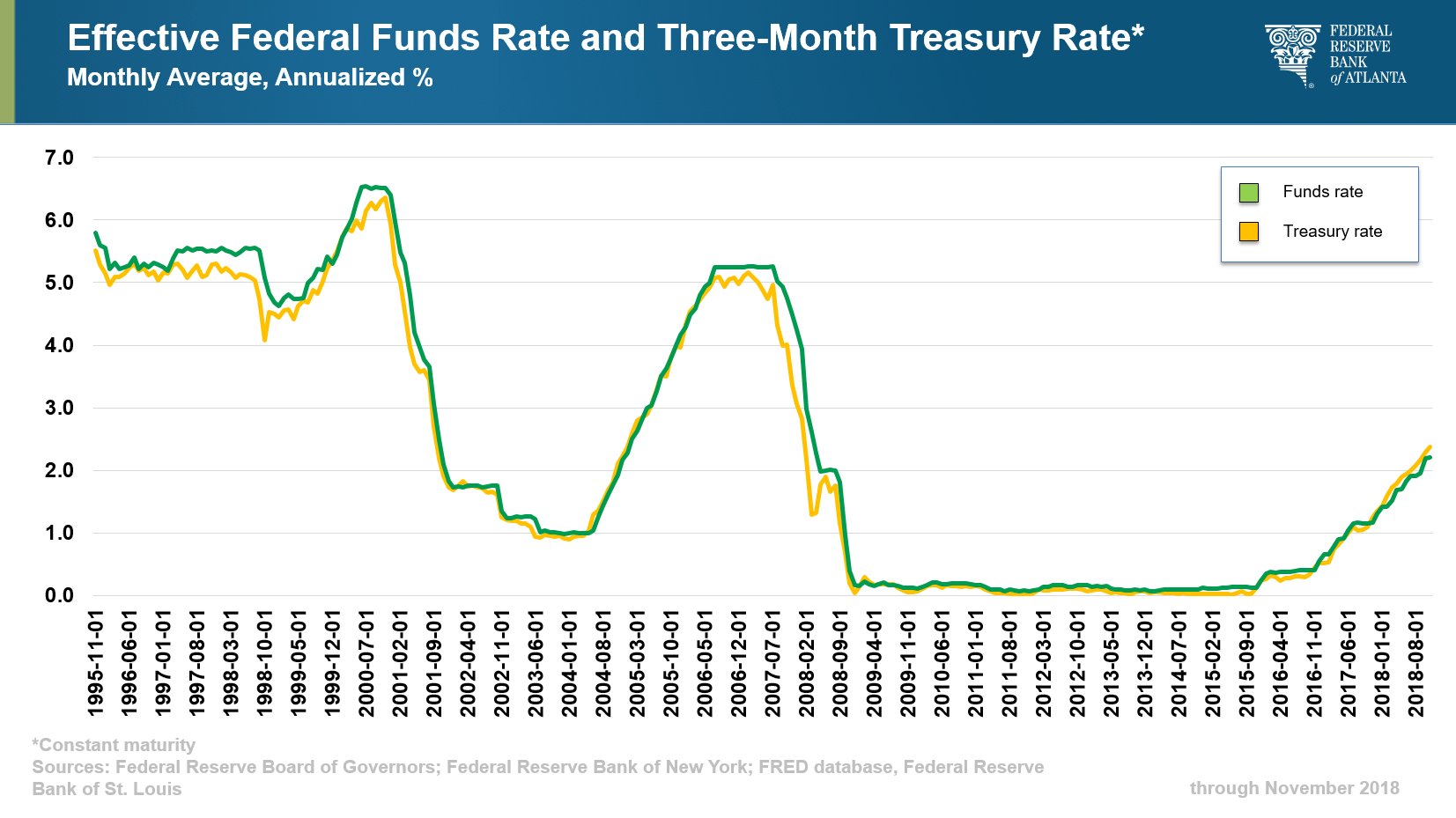

It is apparent that the relationship between the rate chosen to implement policy and the actual value of the federal funds rate has not proven dependent on the reserve regime in place. But a more important question may be whether the transmission of the federal funds rate to other short-term market rates changed as Fed policy shifted from the pre-crisis, limited-reserve regime to the post-crisis, ample-reserve regime. The good news is in this chart: the relationship between the federal funds rate and Treasury bill rates does not appear to differ materially across the period when reserves were limited and the recent period when reserves have been abundant. The same holds true for a variety of short-term rates.

Why I support a floor system

I've now made the first two points I noted at the outset. One, the issue of a big or small balance sheet going forward is largely moot. Two, there has been little discernible difference in the effectiveness of monetary policy over the years the FOMC has operated in a system with ample reserves, relative to the pre-crisis, scarce-reserves regime.

What, then, are the attractive features that would tip the scales in favor of continuing on with a floor system? There are likely others, but I find the following three most convincing: (1) efficiencies in the payments system, (2) robustness during economic stress, and (3) considerations of financial stability.

Former New York Fed president Bill Dudley made the efficiency argument in a 2017 speech. In that speech, Bill noted that a "floor-type system" eliminates the need for banks to trade large volumes of reserves in the process of channeling them to institutions that would otherwise find themselves short on a given day. He concluded that this brand of intermediation has little "social value."

This is, in essence, Friedman rule logic. From a social point of view, reserves are essentially costless to create. Efficiency dictates that the private costs of using reserves should likewise be zero. Eliminating scarcity through abundant reserves is an essential part of meeting this efficiency criterion.

Now let me touch on the robustness case for abundant reserves. As Mary's predecessor and now New York Fed president John Williams has emphasized, the substantial decline in the natural rate of interest over the past quarter-century has introduced the possibility that the effective lower bound on policy rates will become a frequent feature of economic contractions. Even if the central bank maintains a scarce-reserve system during normal times, it is highly likely that ample reserves will have to be engineered amid economic distress, such as during a recession. In other words, if the economy goes south, we'll need a floor system anyway.

There is no logical reason to preclude a framework that switches from scarce reserves in normal times to ample reserves during lower-bound episodes, and back again as a recovery proceeds. But a scheme that, over time, involves multiple transitions from one operating approach to another seems an unnecessary complication, and one that could be difficult and costly for banks and other private-market participants to manage. Given other arguments that favor the floor system, I don't see the return in bearing these complications.

Finally, let me turn to my last point, the potential financial stability benefits of an ample-reserves approach. The case was laid out by Robin Greenwood, Samuel Hanson, and (former Federal Reserve governor) Jeremy Stein at the Kansas City Fed's 2016 Jackson Hole symposium. In that discussion, they focused on a particular threat to financial stability: the tendency for private-sector financial intermediaries to finance risky assets using, in their words, "dangerously large volumes of runnable short-term liabilities."

A larger Fed balance sheet can help ensure an ample supply of government-issued safe short-term instruments, such as interest-bearing reserves. Greenwood and his coauthors argued that expanding the pool of safe short-term claims would undercut the market-based incentives for private intermediaries to issue too many of their own short-term liabilities. In this way, the Fed can crowd out private-sector maturity transformation without compromising the ability of conventional monetary policy to focus on the dual mandate: maximum employment and stable prices.

I will note that the Greenwood-Hanson-Stein proposal is not without controversy. Many of the potential objections were discussed in comments by former Fed governor Randy Kroszner at the Kansas City conference. For example, an uncapped Fed supply of safe short-term assets may actually exacerbate flights to quality—and runs away from private markets—in times of financial stress, adding to rather than limiting the vulnerability of the financial system.

I have myself put the Greenwood-Hanson-Stein financial stability argument in the supporting column of the case for a floor system. But I take the caveats seriously. As we proceed with the existing floor framework, we will need to monitor the performance of the system, and be alert to issues that are not yet apparent.

Conclusion

There remain many open questions as policy normalization proceeds. But this much is certain: the Committee continues to view the federal funds rate target as the primary tool to adjust the stance of monetary policy. The effects of the Committee's interest-rate tools are much more familiar to policymakers and markets than balance-sheet tools are. To my mind, that makes them the superior instrument for reaching and maintaining our dual goals of stable inflation and maximum employment.

Regarding the funds rate, you all no doubt noticed an announcement on Wednesday in addition to the one concerning balance sheet policy. I'd like to guard against misinterpretation of what the FOMC means by patience. There has been some commentary suggesting that the Committee's intention to be patient in adjusting the target range is a definitive signal that there are no circumstances under which we would increase the policy rate for the remainder of the year.

To my way of thinking, that is not an accurate conclusion. I do not view this patient approach as constraining the Committee's options. We may move up; we may move down. I am open to all possibilities as we aim to support sustained economic expansion, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee's symmetric 2 percent objective. Markets should understand that, so I hope I have made my position clear.

Thank you for your attention and for the important work you do.