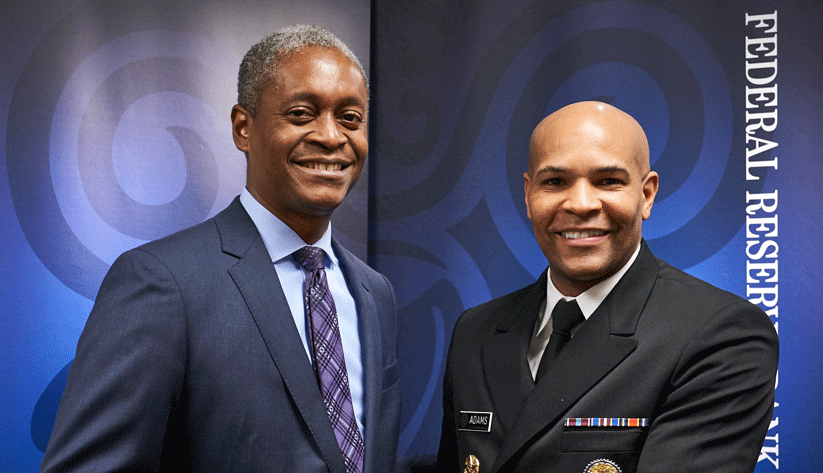

Raphael Bostic: Hello, everyone— my name is Raphael Bostic. I'm the president and CEO of the Atlanta Fed, and it's good to have you here to listen to a conversation I'm going to have with the surgeon general of the United States, Dr. Jerome Adams![]() . Dr. Adams, welcome.

. Dr. Adams, welcome.

Jerome Adams: Wonderful to be here—thank you so much.

Photo: David Fine

Bostic: Well, I'm really pleased that you're here. We have a lot of things in common in terms of our interest in helping communities be more healthy and more productive, and I'm really excited to have a conversation with you on this.

Adams: One of the things I've long felt is that physical health and mental health are directly correlated with financial health, and I'm really excited to be working with the Federal Reserve to show how health equals wealth, and in turn how increasing health for all of society can turn into increasing wealth.

Bostic: We're going to talk a little more about that in a bit, but I wanted to just start with you—you're the surgeon general, and I think a lot of people know that there is a surgeon general, but I don't think they know a lot about what the surgeon general does or how this position came about. Maybe you could talk a little bit about that to give us some clarity on how you got to where you are.

Adams: Wonderful. Well, I wear a uniform, and that's because the surgeon general is the head of the United States Public Health Service Commission Corps, one of the seven uniformed services. Most people, if you ask them on Jeopardy! to name the uniformed services, they could name five of them: Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines, and Coast Guard—if you're really on top of your game. But there's also the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the United States Public Health Service. We're charged with protecting the nation's health, both here and abroad. We've got 6,500 officers all over the country. We've responded to ebola, to earthquakes, to hurricanes, to volcanic eruptions. I'm really proud to serve as the lead of that uniformed service. That's one part of what I do. The other part is the "nation's doctor" role, the part that people are more familiar with when they think of folks like C. Everett Koop![]() or Dr. David Satcher

or Dr. David Satcher![]() , and in that role it's my job to be the nation's top health promoter, to help share with people the science that's out there that will help them make healthier decisions and live longer and healthier lives.

, and in that role it's my job to be the nation's top health promoter, to help share with people the science that's out there that will help them make healthier decisions and live longer and healthier lives.

Bostic: You know, Dr. Satcher is from here in Atlanta.

Adams: Absolutely—he's a good friend of mine. And he is a giant in public health, and Atlanta is lucky to have him.

Bostic: I had the good fortune to meet him a couple weeks ago, and he was absolutely delightful, so maybe I need to make this a quest to meet all of the surgeons general as they go forward. And the other thing that was very interesting—you're a uniformed service. Do you guys have your own hymn, just like the more widely known ones?

Adams: Exactly. We have a Public Health Service hymn that is very much related to our mission, and what we do to protect the health of the nation.

Bostic: Well, that's very interesting. I'm going to go find that hymn when we get done here, and maybe we'll get a link ![]()

![]() to it on this podcast for our listeners so that they can be more familiar with what you guys are doing.

to it on this podcast for our listeners so that they can be more familiar with what you guys are doing.

Adams: That would be fantastic.

Bostic: So I want to turn a bit now to your initiative that got us in touch with each other: the Community Health and Economic Prosperity initiative. Maybe could you say a little bit about what that is, how it originated, and what you're hoping to accomplish from this?

Adams: Absolutely. The goal of our Community Health and Economic Prosperity, or CHEP![]() , initiative is to increase awareness of the connection between community health and business health. We want communities and businesses to know that when they invest their time, their tools, their resources, their expertise in the health of communities, that there are significant rewards beyond the traditional health metrics.

, initiative is to increase awareness of the connection between community health and business health. We want communities and businesses to know that when they invest their time, their tools, their resources, their expertise in the health of communities, that there are significant rewards beyond the traditional health metrics.

I often say to folks that, from a health point of view, we tend to talk about blood pressure or blood sugar or cholesterol levels—but those things don't resonate with CFOs. They don't resonate with individuals who are charged with balancing the business bottom line. We've got to help them understand that by focusing on housing, on food, on physical activity, on complete streets, on clean air laws, that you will see increased productivity at work, that you will see folks who show up on time and are able to be there more consistently, that you will see increased profitability, because unfortunately right now we know that health care is one-fifth of our GDP [gross domestic product], and it's causing companies to move jobs overseas where those expenses aren't quite as high. Workforce health care costs, and even consumers—if you're selling a product to U.S. citizens, and they're having to spend one out of every five dollars to pay for their health care costs, they're not going to be able to buy Christmas presents, to buy cars, to buy the products that generate and stimulate our economy.

Bostic: Or even invest. Money spent on health care is money that's not being saved and not being used for a host of other things that help us be productive. Now, I want to say: we came to this at the Sixth District, because the Sixth District is not doing very well from a health perspective if you look at metrics of health—the five big ones that people often talk about are childhood obesity, adult obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and physical inactivity. If you look at the states in the Sixth District, we're not doing very well at all. Mississippi is ranked number one for childhood obesity—and a higher ranking means you're doing worse—and they're in the top five for the other four metrics. Alabama and Louisiana are in the top ten for all five metrics. Georgia is in the top ten for childhood obesity and physical inactivity, and Tennessee is in the top ten for diabetes and hypertension. The only high performer in our district is Florida, and they still rank in the lower half in terms of health across all these metrics. So it is something that is really important for us and the Federal Reserve, who are concerned about aggregate economic performance. This is a drag on that, and a very significant waste. So ways that we can make progress—it's really important, and I'm really pleased that we've connected to start to try to work together on this.

Adams: And when you think about community building—for instance, the number one cost for most Fortune 500 companies is salary. The number two cost for most of those companies is health care. If I were to tell you, as the owner of a business, that your number two cost is going to be substantially higher in community A versus community B, where are you going to move to? And there's a very real example of this that's played out in the national spotlight recently, when you think about Amazon—Amazon put their second headquarters in Crystal City, Virginia. Well, if you look at Crystal City, Virginia, four of the top 20 healthiest cities in the United States, as ranked by US News [& World Report], are surrounding that Crystal City area. That is not a coincidence. We know that businesses look to move to places where there are healthier employees, and where millennials want to move to because they can live a healthier and more fulfilling life, so you have that talent base additionally. And we want everyone to benefit equitably from this increasing economy, so I think it's important, particularly here in the Sixth District, that folks focus on building community health—not just as a way to live longer lives, but as a way to generate economic development in their communities.

Bostic: So it is true that you'd couch it like that, and I actually didn't know that statistic about Crystal City, so that's very interesting. You talk a lot about the important role that businesses will play in any efforts around improving community health—that's actually a different take than you often hear from surgeons general, in terms of talking about health—like we talked about: finding better food and all that kind of stuff. Reaching out to businesses to try to get them to be a partner in this is quite interesting. What got you to think that that was a strategy that we need to be pursuing?

Adams: Well, Einstein said the definition of insanity is doing the same thing and expecting a different result. And number one, we've got to help folks understand that, yes, there's personal responsibility, and yes, we need individuals to become better informed so that they can make better decisions. But we also know that the decisions people make are 100 percent dependent on the decisions that they have, or that they feel they have, in front of them.

For instance, I live in a pretty decent neighborhood. My kids can go out and run around the neighborhood without fear of getting shot, without fear of getting run over by traffic coming by, and so we can make a choice to be physically active that other folks don't have the option of making. We can make a choice to eat fresh fruits and vegetables because the grocery store is closer than the fast food restaurant, and not everyone can say that. So we need to both help individuals become better educated so they can make better choices, but we need to put better choices in front of them.

And businesses need to understand that they have leverage—unique leverage—that they can bring to bear to help change the environment and create better options, better choices. Many businesses are focusing on employee health care and employee wellness, and that's very appropriate. That said, you can do everything right from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., but if you go home to an unhealthy environment from 4 p.m. to 8 a.m. the next day, you're going to undo much of the progress that you've made. So we need to focus not just on the work site, but on the community. We also know that 50 percent of the health care cost for employers is not for the actual employee, but it's for their spouse, for their children, for their family. So we have to worry about the environment that they're living, working, playing, and praying in, in addition to the employee.

Bostic: I heard you say a statistic some time ago that 80 percent of health is not about health care. It is about things other than health care that affect people's psyche and some of the things you were just talking about. From my background—I'm a geeky economist, so I apologize—we call those the "social determinants of health."

Adams: Yes.

Bostic: Things like housing and the safety of the streets, education, transportation—the things that cause stress in people's lives, and those stresses that lead to people making poor decisions. I say all the time, someone that's under stress is going to make bad decisions, whether you're rich, whether you're poor, or whether you're African American, Latino—it just doesn't matter. How has the health community come to embrace and face that reality: that so much of a person's health is not really about their health care, specifically?

Adams: Well, first of all I think it's important that folks understand that we spend so much of our focus, our time, our energy, our money, talking about health care. And yes, we want everyone to have health care when they need it. But we want to stop fishing people out of the stream after they've fallen in and they're drowning. We want to prevent them from falling in in the first place, and study after study shows that you get much more bang for your buck by investing in those social determinants of health that prevent people from falling in the stream, than you do on the back end. So I'll use diabetes, for instance. We can focus on making sure folks have the most up-to-date medications, that they are refilling their medications—and that's important. But wouldn't you much rather prevent diabetes on the front end by helping people be physically active and eating right, than to have to deal with their diabetes on the back end? If it were you, personally—wouldn't you rather not have diabetes in the first place, than to have access to top-notch medical care to treat your diabetes after you've already developed it?

All those things are critically, critically important. And again, employers can get involved with policies in their communities. They can show up when they're debating clean air laws, they can show up when there are debates about zoning, they can show up when there are discussions about whether or not we should build a park so that people can commingle together and can exercise. And they can also do some of these things on their own work site, where you can promote these social determinants of health by making the healthy choice the easier choice for individuals: the choices you're making in terms of vending machine policies, in terms of what you're carrying in your cafeteria, in terms of just looking around, walking around your work site, and asking yourself: Are your stairs accessible? I was here at the Federal Reserve and checked out your stairwell, and you all are doing some great things here where you've made the stairwells more attractive, more well-lit, and have artwork in there, so that folks can find them in the first place and would rather take them than take the elevator.

Bostic: That's a new thing that we put in probably six months ago to try to make the stairs more appealing. There are fun facts in there, it's painted, it's well lit, and the idea is really to try to help people use the stairs far more often, because those are hidden calories that you can burn that makes it much easier, without having a lot of extra time.

Adams: Have you read the book called Nudge?

Bostic: No, I have not read that.

Adams: It's a great book that talks about things that we can do, and it's not just about health. They talk about getting people to invest more money, and the fact that in many cases the default option for folks is what they go with, but our default options are not the healthiest financially, physically, or emotionally. And so, we don't want to create a nanny state—make no mistake about it, that's not what we're advocating for here. But what we're advocating for is nudging people in the right direction, giving them more options, and then making the options that we know will be better for them and for society the easy option instead of making it the harder option to pursue.

Bostic: And one thing on this that I think it's important to understand: there are some things we know work. There are things that we know are better for people's outcomes, and we're not going to make anybody do that, but we should make it known that those things work, and then we should try to make it as easy as possible to do those things. You talked about prevention as opposed to treatment. Preventing something rather than treating it is often cheaper often leads to higher quality of life. The story that I think about in my background is homelessness. We know that it is far cheaper to do the interventions before someone's homeless than after they're homeless. That has become much more widely known among policymakers, and so funds for homelessness prevention have become very highly protected. There are a whole bunch of other areas where that knowledge is not as clearly known, and I think that we have an opportunity to try to change an understanding and then lead to a different outcome.

Adams: And this is where you all can really lean into this, as folks who are experts in finance. We need to restructure the payment system, because you and I agree completely that prevention is cheaper. The problem is, for whom and in what system? And you asked about health care delivery. I'll give you, again, a very real example: hospitals don't get paid to keep a diabetic out of the hospital. Hospitals get paid every time that diabetic walks through the door and shows up. There's another saying—that every system is perfectly designed to get exactly the results that it gets. We need to restructure our financial incentives, our payment systems, so that people are paid to stay healthy and not paid to be unhealthy. The only person for whom right now it is clearly a cost to not prevent disease within the health care system is the federal and state governments, because ultimately they're the ones, along with employers, who have to pay the ultimate cost. But within the health care system most folks get paid to do the wrong thing and not to do the right thing.

Bostic: Well, people respond to incentives, and they know how they get paid. This is an issue that is pervasive and is one of the challenges, in fact, in dealing with the social determinants of health. In many programs, health dollars can't be spent on those social determinants, and it makes it much more difficult to make progress in those things.

Adams: And employers can look at their benefits structure for their employees, and make changes or ask questions. Another great example that everyone's talking about is the opioid epidemic. Have you looked at your benefits structure lately and asked yourself, "Are we paying to prescribe opioids versus paying to give folks alternatives for pain management to opioids?" We know that four out of five heroin users got started with a prescription opioid. We know the U.S. prescribes 90-plus percent of the world's opioids to less than 5 percent of the world's population, and a lot of that is funded by our insurers, by employers out there. So there are real things that folks could be doing right now to change the system and to change the incentives in the system.

Bostic: I was going to raise the opioid crisis, because again—this is something that is very present in the Sixth District. As you look across the Southeast, it's in a lot of places. I know this is something you've spoken a lot about and you've spent a lot of time on. How are we doing, and what are your prospects for making progress on this?

Adams: Well, it's definitely something I'm passionate about. It's pressing, but for me it's also personal: my own brother is in prison right now. He stole money to support his addiction and got a 10-year prison sentence. And I tell his story because it's the story of someone in every community across America. If this could happen to the brother of the surgeon general, it can—and it is happening—to all of us. I'm very concerned about where we are as a country right now. For the third year in a row, we've seen life expectancy not increase. Let me put it a different way: I represent the first generation of parents—I have a 14-, a 12-, and a 9-year-old—the first generation of parents in the last half a century who can't tell their kids that you're going to live a longer life than what your mom and your dad did.

That said, we are making progress. We see medication-assisted treatment become more available to folks. We've seen naloxone prescribing increase by 350 percent. The federal government, state, and local governments are leaning into this issue like never before, and my challenge to folks is not to look at the opioid epidemic simply as a fire to be put out, but to look at it as an opportunity to bring folks together to talk about the issues that ultimately lead to health and wellness in our communities, and both put the fire out and prevent the next fire from flaring up again. But your listeners out there can do something. Go to surgeongeneral.gov![]() and download my digital postcard that lists five steps that everyone can take to respond to the opioid epidemic. We all have a role to play, and if we don't all do our part then we're going to be dealing with this issue for a lot longer than what any of us would like.

and download my digital postcard that lists five steps that everyone can take to respond to the opioid epidemic. We all have a role to play, and if we don't all do our part then we're going to be dealing with this issue for a lot longer than what any of us would like.

Bostic: Well, I'm glad that you said that because in so many instances we think of it as somebody else's problem, and I'm not involved, I'm not engaged. And for many of the issues that we're talking about, it's everybody's problem. We all actually pay extra when things don't work, and we all can be adversely affected by it—it's a pretty significant thing. And I'll just tell you, for the Federal Reserve System: I'm the chair of the Committee for Human Resources now, and we are now looking at all of our benefits to see if we, in our structure, are promoting elevated use of opioids that may be not necessary. And so it's led us to question, in a lot of ways, how we should think about this.

Adams: You talked about human resources. Human capital is a big issue. We have six million unfilled jobs in this country right now—more unfilled jobs than there are people looking for work. I don't mean to be an alarmist, but we literally, in my opinion, have a workforce crisis, and companies are going to have to make tough decisions about whether we stay here and wait it out and hope that we can eventually hire people or whether we start moving some of these jobs overseas. We really risk having our economy stall if we don't pay attention to health—and in particular the opioid epidemic, which is causing so many people to check out of the workforce.

Bostic: You know, we have a new center—I guess it's not so new, it has been a year—on workforce development and economic opportunity [the Atlanta Fed's Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity], precisely because we see the economy evolving in ways where we could have shortages in our workforce in a number of categories because our current workforce doesn't have the skills to fill those jobs of tomorrow. So we're trying to get employers to be more sensitive to this, speak out more about what they need, and we're also trying to talk to educators, community colleges, technical schools and the like to see what they're doing to create programs so that we can give people pathways into those new jobs. And folks who have already checked out because they're now addicted to opioids, and folks that are at risk of that—

Adams: They have a criminal record and have difficulty in finding employment for that reason...

Bostic: There are many categories where we need to think creatively about ways to get them to be fully engaged in our workforce, so that we can remain competitive at the global scale—because that's where we are right now.

Adams: And it's not just finances—it's our national security. Another shocking statistic, Raphael: seven out of ten of our 18- to 24-year-olds are currently ineligible for military service in this country because they can't pass the physical, can't meet the educational requirements, or have a criminal background record. Our economy is not achieving all that it could be because of our nation's poor health. But we are also literally a less safe nation than what we could be because of our nation's poor health. It isn't just health for health's sake that we need to worry about. If we're worrying about the future economic prospects and safety and security for our children and our grandchildren, we need to really start leaning into these social determinants, these community determinants, of health.

Bostic: I want to just make a little turn here, and I know we're running out of time. So you started off in biochemistry and psychology, right?

Adams: Yes.

Bostic: So, hardcore science. You've got a master of public health degree from the University of California at Berkeley, you got your undergrad at Maryland, and then you got a medical degree from Indiana University.

Adams: You've been talking to my mother, haven't you?

Bostic: Absolutely. [laughter] I've got to do my research, right? So that's all service, in terms of delivering a service, from the medical. What got you to move into the public sector, and to take on more public roles?

Adams: Well, that's a great question. I love practicing medicine. There is no greater feeling than staying up all night with someone in the operating room and feeling like you've saved a life. And as surgeon general, I still practice about one day a month at Walter Reed [General Hospital]—because again, we need people there. Sometimes people are just going to fall in the stream, they're going to fall in the river, and they need to be fished out. And someone needs to be there, committed to fishing them out.

But that said, I've found that by getting involved in public service I can help a thousand people—ten thousand people—a million people—at once, versus the one-on-one care that I can provide in the operating room. And I'll give you a very real example of this: I worked at a Level I trauma center for the last ten years. We literally saved lives. People would come in with multiple gunshot wounds and car wrecks, and at the end of the evening you would say to yourself, "If I hadn't been there, that person might not be alive today." But in my ten-plus years, I've maybe really been critical in saving five hundred, a thousand people's lives. Well, earlier this year as surgeon general we put out an advisory letting folks know what naloxone is—it's an opioid overdose-reversal agent—and helping them understand that in all 50 states, third parties can carry naloxone and respond to someone who's having an overdose. Since that happened, naloxone prescribing's up 350 percent. So to put it in real numbers: I have saved, literally, exponentially more people in six months, with a public health intervention and with my advocacy, than what I saved in ten years of medical practice. And it's not to diminish or lift up one over the other, but it's to show that impact that we can have if we get involved, if we lean into policy change, if we all try to figure out how we can, in our own lives and our own unique ways, become public servants.

Bostic: But policy change is hard, right? And that can take a long time, and there's no guarantee of that. So you've now been in Washington for a little more than a year.

Adams: Yes.

Bostic: And after being the health commissioner in Indiana—

Adams: For three years, yes.

Bostic: For three years. And Indiana had some issues, while you were the health director, in HIV and a number of other things, so you've been under the spotlight. Is it different? How has this role compared to some of the things you've done in the past?

Adams: My time in Indiana as a state official led me into the Washington, DC world with my eyes a little bit more wide open, but nobody is prepared for living in the bubble of Washington, DC—having every decision that you make, no matter how neutral you think you are, instantly classified into being either right or left, either Democrat or Republican. And what I've tried to do is just always stick to my mantra of doing the right thing, of not assuming that anyone can't contribute to the conversation. And I think that's one of the problems we have right now—we shut down people, we refuse to listen to them, to hear from them, and no one's got a monopoly on good ideas, and no one's got a monopoly on bad ideas, either. So we need to make sure we're talking to everyone and engaging them and building that trust.

And I saw it happen in Indiana. It took time, it took time. But over my three years there, we were able to bring people together to gain trust, and I'm seeing it happen here in Washington DC, largely with the unfortunate wind of the opioid epidemic in our sails. Now folks are realizing we can't stay in our corners and overcome this problem—we've got to come together.

Bostic: Well, health is certainly not a partisan issue, and you're not advocating for it in that way. It's really gratifying to see someone in your position reaching out and engaging a whole range of people in the service of trying to improve people's health. And that is something that I'm appreciative of, and the country will benefit greatly by. I've been talking with the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Jerome Adams. Jerome, it's been a pleasure to talk with you. Good luck, and I look forward to working with you a lot in the future.

Adams: Absolutely. Thank you, and remember—health is wealth.