Editor's note: This is the second in a series of articles on transit-oriented development.

Residential complexes going up near Atlanta transit stations promote pools, leash-free dog parks, and lifestyles "where urbanity meets savvy simplicity." If these amenities don't evoke the gritty utility often associated with public transportation, they've achieved their desired effect.

The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) is at the forefront of the Southeast's small group of transit agencies pursuing transit-oriented development, or TOD, near its stations. MARTA's core objectives with these projects are increasing ridership and revenue for the transit agency and supporting local and regional economic development.

MARTA's Amanda Rhein.

Photo courtesy of MARTA

A common complaint about MARTA is that its heavy rail system doesn't provide easy access to enough popular destinations, noted Amanda Rhein, MARTA's senior director of transit-oriented development and real estate. Because the developments seek to make living near rail stations appealing, they are one way to address that issue. However, MARTA also views the developments as "pedestrian experiences" and envisions them as a pleasing "first and last mile" leading to trains and buses, explained Rhein.

"It's about bringing more people into the immediate vicinity of the stations, but also creating destinations that are transit accessible," she said.

Transit-oriented development is growing more popular across the country. Transit agencies such as MARTA hope to convert underused real estate into ridership and revenue generators, in the process enhancing sales and property taxes for local governments and returns for private developers who buy or lease the agency's land.

But designing these properties to achieve the myriad goals planners attach to them is a complex undertaking. Those goals, in addition to enhancing revenue and ridership, include addressing the shortage of affordable housing that plagues Atlanta and cities across the country. MARTA requires 20 percent of residential units in its developments to be affordable to households earning 80 percent or less of the area median household income. (See part 1 of this series for more on affordable housing and TODs.)

Atlanta a good laboratory

Transit-oriented development may be particularly relevant in metropolitan Atlanta. Roads are already heavily congested, and another 2.5 million people will live in the area by 2040, according to projections from the Atlanta Regional Commission and other organizations. Second, Atlanta has a more extensive rail transit system—48 miles of heavy rail—than many Sunbelt metros.

Metro Atlanta holds the dubious distinction of having some of the country's worst traffic, according to a report from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. And although MARTA's 39-year-old rail system lacks the network of tracks of older northeastern cities, the rail service is the most robust in the Southeast.

An example of one of MARTA's transit-oriented developments. Photo courtesy of MARTA

An example of one of MARTA's transit-oriented developments. Photo courtesy of MARTAWhat MARTA is doing

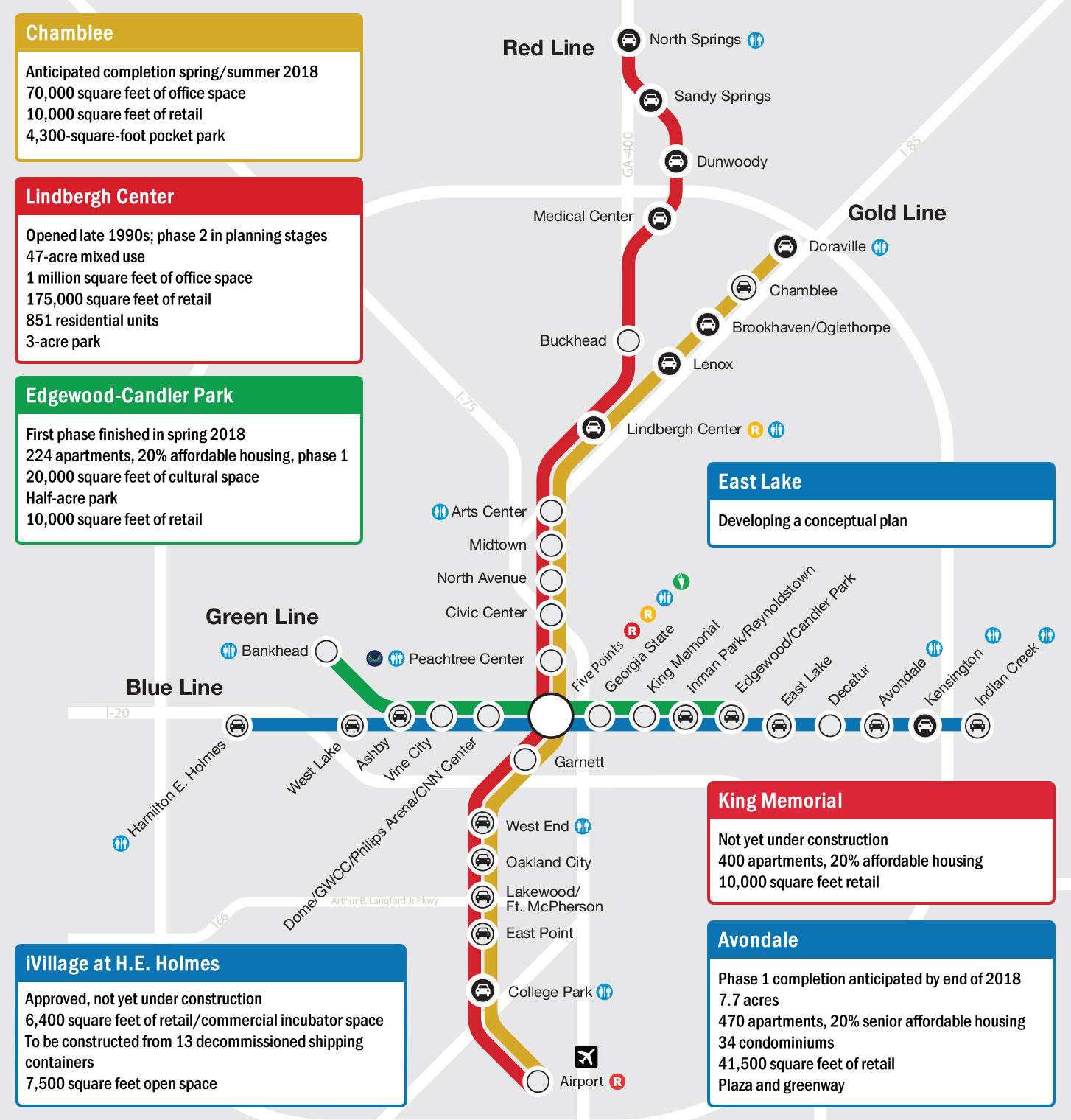

MARTA currently has three transit-oriented developments under construction and four more in the planning stages. Two of the developments going up now are primarily residential complexes that include street-level retail and greenspace. One of these, at the Edgewood-Candler Park Station east of downtown, is partially complete and already has residents in its apartments. Another, at the Chamblee Station just northeast of Atlanta's city limits, will include mostly office space with a small retail component.

MARTA completed its first TOD nearly 20 years ago. The Lindbergh Center Station development encompasses apartments, office buildings, and retail spread over 47 acres (see the map). However, the Lindbergh Center Station development came years before MARTA adopted a concrete TOD strategy in 2010.

Indeed, because MARTA real estate development on a broad, strategic scale remains in its infancy, Rhein said the effects of its transit-oriented developments cannot yet be gauged. And drawing conclusions from established TODs in other metros about what might work in Atlanta is difficult, she pointed out, as each metro area has different development patterns, population growth trends, and other relevant characteristics.

For those reasons, MARTA is not trumpeting any grand expectations. The agency does not offer TOD-based ridership projections, Rhein said. But it has published other forecasts. Phase one of the Spoke project adjacent to the Edgewood-Candler Park Station, for instance, will generate $500,000 a year in new property taxes for the city of Atlanta and DeKalb County, according to MARTA. A few miles farther east, the Avondale TOD, MARTA says, figures to produce $800,000 in annual tax revenue for the city of Decatur and DeKalb County.

Traffic congestion could threaten future prosperity

MARTA's development plans are not solely aimed at relieving traffic jams, but that goal is implied. Congestion results mainly from growth in employment and population—a natural side effect of a prospering local economy—yet sustained economic growth and quality of life hinge in part on managing traffic congestion.

Economists don't have a consensus about how much traffic congestion impedes economic growth. At the same time, extensive research warns that if traffic gets bad enough, it can restrain a local economy. A 2017 report from the United States Conference of Mayors and the Council on Metro Economies and the New American City concludes that if congestion in the largest metros does not improve, it will threaten future economic growth both locally and nationally.

"I wouldn't expect places like L.A. or Atlanta or Dallas to ever completely stop growing because of congestion," said Chris Cunningham, a research economist at the Atlanta Fed. "However, these places could grow faster, earn more money, and be more productive if they were less congested."

Rhein believes metro Atlanta needs to accommodate future growth more sustainably than the sprawl-producing, automobile-oriented model allows. "It really does need to be a combination of transportation and land-use decision making," Rhein explained. "And TOD makes the most sense if that's the problem you're trying to solve."

Still, such developments aren't a silver bullet for reducing congestion. They are a tool with potential, though. Research by Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic and Marlon Boarnet of the University of Southern California found that in Los Angeles, households that move to within a half mile of a rail station would drive about 15 fewer miles a day, on average.

Worthy but complex goals

While most would probably agree MARTA's TOD goals are worthy, achieving them is far from simple.

To start, most people don't use transit. National transit ridership remained essentially flat for decades and declined since 2014 (see the chart). The picture is broadly similar for MARTA. Ridership was stable for the past five years. But the 2017 passenger count was 15 percent lower than in 2007, though metro Atlanta added about 600,000 residents in the interim (see the chart).

Increasing transit ridership presents stiff challenges (see the sidebar, "Reducing Driving, Boosting Transit a Tough Task"). Many factors that determine transit use—such as the rates of private vehicle ownership and use, gas prices, and population density—are largely beyond the control of transit agencies, according to Brian Taylor and other urban planning faculty members at UCLA. Taylor and colleagues Michael Manville and Evelyn Blumenberg wrote this year in the Journal of Public Transportation that despite new, high-level services and more TODs, demand for transit will likely fall under any of the following conditions:

- a population grows disproportionately outside the largest metropolitan areas or on the suburban fringes within these areas

- households that traditionally drive little get more access to automobiles

- fuel costs fall, cars become more reliable, or other costs of driving decline

- affordable and convenient chauffeuring and ridesharing services emerge

Research shows that the surest way to reduce automobile use, and presumably boost transit ridership, is to raise the cost of driving.

Drivers crowd onto highways because the limited supply of road capacity is typically free. Measures to "tax" driving are not widespread in the United States. Instead of using such sticks, U.S. states and localities generally offer carrots such as more bus and train service and bicycle lanes.

Some jurisdictions have instituted a limited form of "congestion pricing." These experiments include tactics such as high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes, which charge a fee for single-occupant vehicles to drive in them. Results have been mixed: carpool and transit use has increased in some places and decreased in others, according to research in the Journal of Public Transportation. As for full-fledged congestion pricing, London operates a program in which drivers must pay 11 pounds, about $14.75, to drive in the central city between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. Singapore and Stockholm also use congestion pricing to manage traffic and reduce emissions.

Unlike roads, rail that has exclusive use of its right of way improves up to a point with heavier usage, noted Chris Cunningham, a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. The more people who ride the train, the more frequently the transit agency can afford to run them. Wait times get shorter, and riders’ transfers among trains get easier.

But increasing transit ridership is not easy. Many researchers have noted the substantial gaps between the large numbers of people who support transit in polls and the far smaller numbers who actually use it. Some research argues that transit policy and investment tend to focus less on the needs of core users—who tend to be low- and moderate-income earners who ride buses as well as trains—and more on the interests of more affluent commuters. This focus may reflect the desire to attract riders who could otherwise drive private cars, which can increase transit ridership. But it may also reflect local political forces, Cunningham noted.

Promising signs amid challenges

Given TOD's complexity, it's no surprise MARTA has had a few setbacks. It canceled one project at its Brookhaven Station after squabbles erupted among local government agencies, private developers, and other stakeholders. Other proposed developments have faced delays. And although the Lindbergh Center development has been largely successful—some even credit it for contributing to the surge of building along the Atlanta BeltLine pedestrian and bicycle path—it has not achieved all MARTA's original goals, the agency explains in its master plan. For example, the retail element of the original plan has not materialized "in a commercially sustainable way," and the development ended up with more parking decks than the agency's principles call for.

Still, the marketplace appears to be showing the importance of proximity to MARTA rail stations. Numerous media reports and industry analyses herald an apartment construction boom near MARTA stations, and corporations seeking to relocate emphasize the role of transit access in their decision-making process.

Moreover, office rents in buildings within a half-mile of MARTA rail stations were on average 25 percent higher than those in the overall metro Atlanta market during the first quarter of 2018, according to a report from Cushman & Wakefield, a corporate real estate services firm. In a news article, a Cushman & Wakefield official said proximity to MARTA is a key factor but not the only reason for that rent premium.

Either way, more office space built near MARTA rail stations is probably a good sign for the agency. Some studies show that concentrating employment near transit likely does more to increase ridership than does clustering housing at stations. The Center for Transit-Oriented Development, a partnership among economic consulting, planning, and development groups, attributes this effect to the large share of all transit trips that are work-related. Even though research shows the share of work trips has declined since the early 1980s, employment centers hold the potential to generate new ridership, furthering MARTA's goal of increasing transit-accessible destinations.

It might take years for the results of MARTA's TODs to be apparent. For now, though, Rhein said she's pleased with the agency's real estate development work. "If we're giving people a reason to use the system and a reason to get on the train when they never have, then that's progress," she explained. Perception also matters. Working to better use property and generate revenue, she adds, "shows we're doing everything to leverage resources to operate the system and be good stewards of taxpayer dollars."