COVID-19, Workers, and Policy

Stuart Andreason

March 18, 2020

2020-02

https://doi.org/10.29338/wc2020-02

Download the full text of this paper (904 KB)

As coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) spreads around the world and across the United States, many policymakers and public health officials are encouraging employers to tell workers to work remotely or to stay home when they or their family members are sick. There are significant questions, though, about how many people can work from home. Many U.S. workers in retail, restaurants, manufacturing, and other occupations cannot do so. This Workforce Currents post will explore who can work from home and identify practices and policies to support workers who cannot work from home in the event of a pandemic like COVID-19. It will end with a policy focus on the potential of short-time compensation as a response to workers who have to self-quarantine.

Who can work from home?

While many workers can and will work remotely—regardless of a public health crisis or a natural disaster—many workers cannot. It would be difficult to serve food, sell retail items, or even help care for sick patients over video conference.

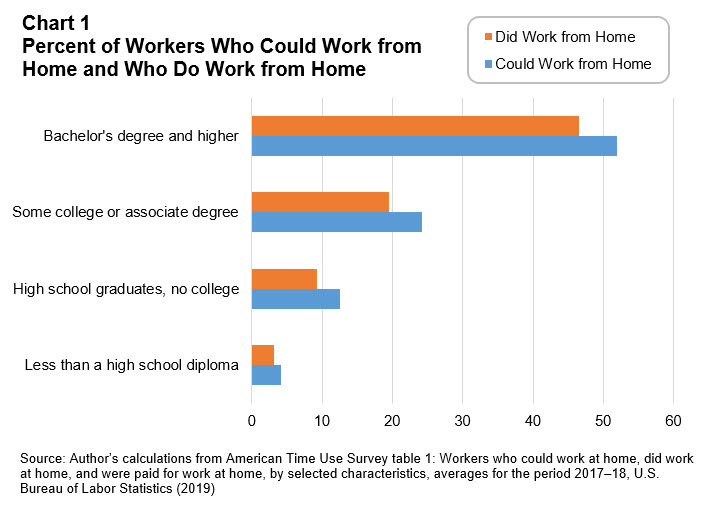

In fact, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that less than 30 percent of workers can work remotely. That has significant implications for workers who need to miss work for an extended time, particularly in the case of a public health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic. Not surprisingly, workers who have less education are less likely to be able to work remotely. Chart 1 shows the percentage of workers able to work at home by educational attainment.

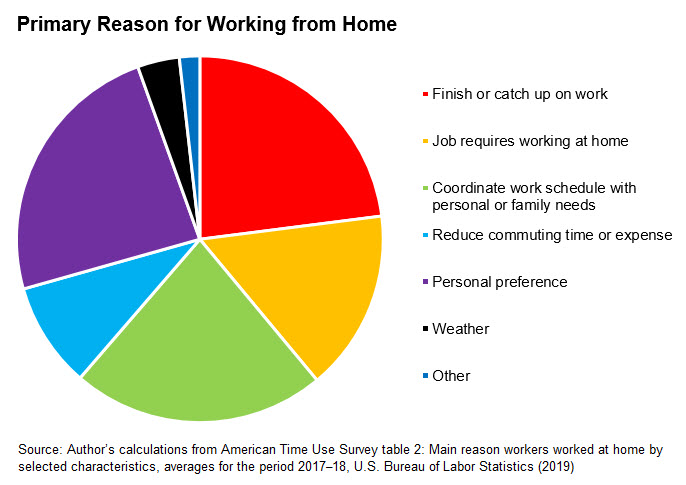

The differences in both ability and opportunity to work from home are significant. In terms of responding to a public health crisis, it is important to focus on the ability to work from home rather than on the percentage of people who do work at home. The American Time Use Survey captures workers who work at home periodically or occasionally, and often even for a small portion of a day. The pie chart shows the primary reason workers may work from home. It suggests that some workers may not be able to work from home for extended periods; their work may include patient or client contact that has to be in person with only some administrative tasks able to be done remotely. That is particularly seen among the 23 percent of workers who work from home to finish tasks.

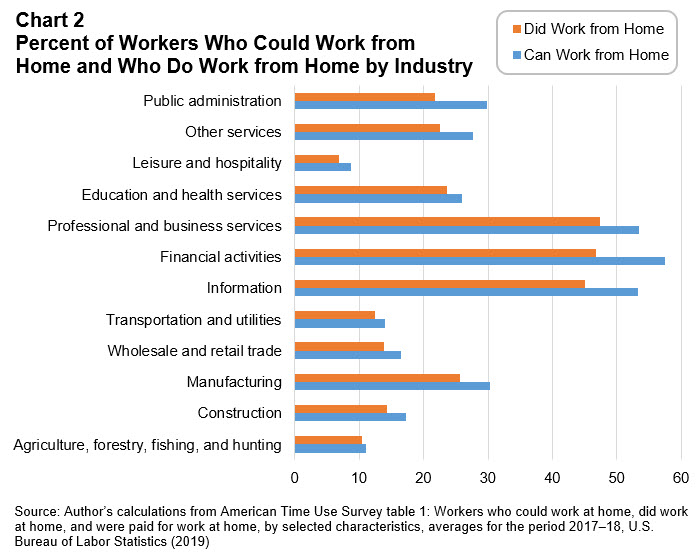

These numbers suggest that working from home is simply not an option for many workers and many firms cannot accommodate work-from-home arrangements.1 Different industries can make this more or less possible for workers. Chart 2 outlines differences in work-from-home ability for workers. Workers in professional fields and typically white-collar work can and do work from home at substantially higher rates than workers in other industries. As expected, leisure and hospitality workers work from home at among the lowest rates across industries—less than 10 percent of those workers have an ability to work from home.

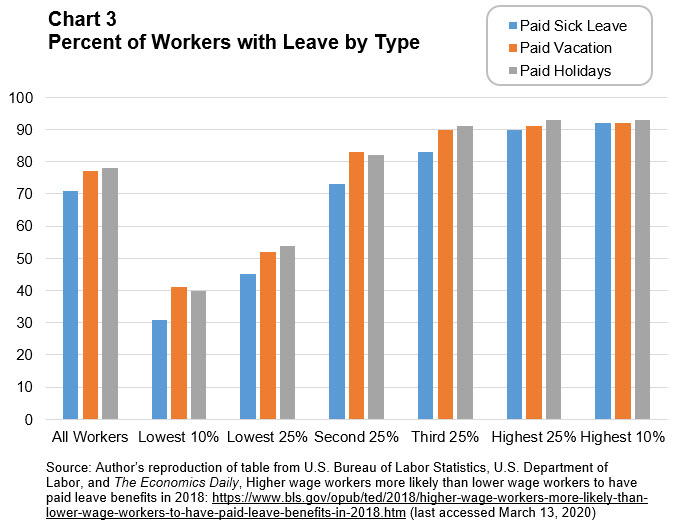

In addition to considering the ability to work from home, it is important to consider how workers would manage leave due to a sickness, infection, or quarantine during a pandemic or other catastrophic event. Some employees receive employer-sponsored sick time or paid leave. Chart 3 shows the share of workers who have paid time off available through their employer. Lower-wage workers have significantly less access to paid time off, particularly paid sick leave. Less than half (45 percent) of workers in the lowest-wage quartile have paid sick time off; that number drops to 31 percent for workers in the bottom 10 percent of pay.

The data do not suggest that time off for sickness would adequately cover a quarantine period. Many employers have small sick-time allotments that would not cover a quarantine period. Many employers also grant sick time through a tenure-based system where workers earn time the longer they work, potentially leaving shorter-tenured workers without leave. Caps on sick time may not cover a quarantine period, either.

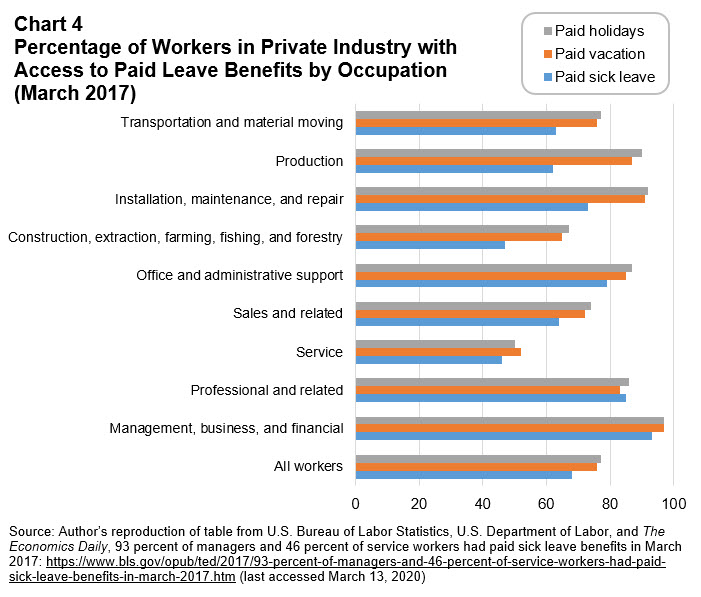

Also, the availability of sick leave varies significantly across industries and occupations. Chart 4 shows the differences by occupation. Not surprisingly, service, construction, and agricultural workers have lower access to paid time off. Overall, only 68 percent of workers have sick leave.

How can practices and policies support workers who cannot work remotely?

Given the number of workers who do not have access to remote work or paid sick leave, it is critical to consider practices that support this population as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic work their way through the country and economy.

Employer practices that can support workers during a quarantine

Over the first several days of March 2020, many employers created flexible leave policies, paying the wages of workers infected or quarantined with COVID-19, and offering job protections for workers affected or quarantined. Anecdotally, these firms are larger and often multinational in scale, and they have resources that many smaller firms simply lack. Employers have shown a propensity to support workers for public health purposes and because it is a good thing to do, but some firms do not have the financial capacity to deal with the losses in productivity and earnings associated with employees out of work. An overall longer-term expansion of access to paid time off would similarly help workers in future situations.

Employer practice is only one portion of responding to the challenges of a public health crisis and adequately protect workers and allow them to recover safely. Policies and public supports need to fill the gap.

Existing policies that can support workers during a quarantine and lower overall demand

Paid time off: The most often mentioned policy to support workers in the time of a quarantine is paid family leave or paid sick leave—and many states and localities have some form of mandated paid family leave policy. Some of these would cover workers in a quarantine situation, but many workers would not be covered.

For example, the city of San Francisco's Paid Sick Leave requires that workers earn one hour of sick leave for every 30 hours worked, with an optional employer cap of 72 hours for firms that have over 10 employees and an optional cap of 40 hours for firms with less than 10 employees. To reach the cap at a firm of 10-plus employees, a worker would need to work just over one year—54 weeks. A worker at a firm of under 10 employees would need to work over six months—30 weeks—to reach the cap of 40 hours of leave. While both leave caps in San Francisco are short of covering two weeks off of work (roughly what would be needed for a 14-day quarantine), workers at a small firm would find themselves with only half of the sick time they need for a quarantine, assuming they had a full allotment and hadn't experienced any other illness or time off prior to taking time off due to a quarantine.

Paid time off policies can cover some of the gap for workers unable to work from home, but as constructed, they do not represent full coverage across the country or full coverage of a 14-day quarantine period, in many cases.

Family and Medical Leave Act: While the Family and Medical Leave Act provides job security for workers who may be quarantined, sick, or supporting a sick relative, it does not provide compensation or help a worker pay for daily life while out of work.

WIOA Rapid Response: The U.S. Department of Labor in coordination with state workforce development boards can administer rapid response services both as a result of a layoff as well as in anticipation of a layoff. Rapid response staff help to coordinate public and private resources and services to mitigate the impact of layoffs or planned layoffs. The services include job training, referrals to different employment, and income supports. Rapid response staff help to avoid future layoffs by working directly with employers to provide training, manage employment regulations, and identify incumbent worker supports.

WIOA National Dislocated Worker Grant: These discretionary grants from the U.S. Department of Labor cover supports for workers dislocated by layoffs, natural disasters, and other events. These grants can cover a number of supports for workers, and can include self-employed, contract, and gig workers who find themselves unemployed or significantly underemployed as a result of an emergency or disaster.

Unemployment insurance: Some firms will have to lay off people due to limited demand for products and services. When that happens, employees may be able to file an unemployment insurance claim for that period. Unemployment insurance varies from state to state, but typically pays for 60 percent of a worker's earnings when laid off—with a cap on weekly benefits. In California, for example, the minimum benefit is $40 per week and the cap is $450 per week. Unemployment insurance is likely an option for workers at firms that have to shut their doors completely due to COVID-19 or other public health crises. While the firm may reopen eventually, during the layoffs and business closures, employees can collect unemployment insurance to support their lost wages.

Short-Time Compensation (STC) or Work Sharing: The STC, a lesser-known program that is part of the unemployment insurance program, offers significant opportunities to support workers during a public health crisis like COVID-19, where workers will be out of work only temporarily and their firm continues to operate. Rather than lay off that worker, in the STC program workers are compensated for reduced demand and work hours. The program was initially created to help firms keep workers employed during recessions or major drops in demand. For example, a firm might reduce workers' hours from 40 to 32 hours per week and continue to pay workers for the 32 hours they worked at their full rate. Meanwhile, the STC program would pay unemployment benefits to workers equivalent to 20 percent of a workweek's pay. That allows the firm to avoid laying off 20 percent of its workforce when it is experiencing low demand. Often layoffs of that type are made inefficiently due to the unemployment insurance program we have in America, which largely requires firms to sever relationships completely with workers before any support is available.

The concept of short-time compensation has been discussed in the United States since at least the 1980s, but it has made only small inroads into our unemployment insurance programs. While small, it has had significant effects. Current U.S. Department of Labor estimates suggest that it has saved over 500,000 people from layoffs since the Great Recession.2 Right now, 26 states have operational STC programs and law to support them (see the list of states below).

Policy focus on short-time compensation and COVID-19

The following section will dive into the policy details of applying the short-time compensation program to workers who are in quarantine.

The short-time compensation program is designed to help support workers in reduced demand periods. It is well constructed to support workers who are dealing with fewer work hours due to a public health crisis. It can cover lower wages due to lost hours at work for up to 26 weeks. As constructed, the program can accommodate payments for reduced hours between 10 percent and 40 percent of a workweek. The benefits are crafted and computed based on a workweek. To support responses to COVID-19 and other public health crises where someone would have to be out of work for an extended time rather than down hours, the program would need to be adjusted to be paid roughly monthly rather than weekly.

A five-week computation for benefits would likely work well and require few administrative changes to the law. Assuming that a worker misses 10 of 25 workdays due to a quarantine, the STC benefits would fall into the existing threshold for the law.

Modeling STC for a $40,000-a-year worker

Assume a female hospitality worker in California who makes $40,000 a year contracted COVID-19 and had to be quarantined. The worker's typical weekly wage is about $770 a week. Over five weeks, her typical earnings are $3,850. While she would still be able to work full-time for three weeks of the time frame, she would be in quarantine for two weeks and thus unable to work at all. For those two weeks, the worker would receive a STC benefit of $450 (she would be eligible for $462, but the California state cap on unemployment insurance benefits reduces her benefit by $12 each week). In total, absent any other support from her employer, the worker would lose $640 in wages during the quarantine period instead of $1,540. This helps make it possible for the worker to keep up with rent, car loans, and more.

The benefit to society would be that a sick worker was able to stay home and limit the spread of the virus. As for the worker, she would not be laid off and could return to her job and return to being productive. In addition, it keeps employees engaged with work rather than having to be out of work for a period of time.

The costs to the government of the STC program may be smaller than the estimate above, as some portion of the STC-paid quarantine period would be covered by employer-paid sick time. Similarly, the $640 cost could be smaller to the worker due to employer supports. Employers or state and local governments may even step in to cover the relatively small 40 percent gap for workers in that period.

While a much more extensive analysis on the public health benefits and costs to the STC program would be needed to make this claim, it is likely that the benefits to paying the STC filing and even potentially a $640 gap would be funded through reduced health care costs associated with the spread of the virus.

STC and contract workers

The STC strategy to support workers who need to be quarantined currently applies only to employees. It does not cover gig workers, contractors, or other workers who receive a 1099 tax form rather than a W2 because of their eligibility for unemployment insurance. Longer-term discussions should help to address similar challenges for workers who aren't eligible for unemployment insurance or the STC program. See the U.S. Department of Labor Office of Unemployment Insurance Short-Time Compensation Fact Sheet for a list of states with a program in place.

The challenges that COVID-19 presents for workers and firms are significant and complex. Public policy and programs like the short-time compensation program can support workers through challenging situations like a 14-day quarantine and fill the gap for potentially lost wages.

Stuart Andreason is the director of the Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity.

_______________________________________

1 In this survey, reported percentages of workers with a bachelor's degree or higher are above estimates for other data sets. Nearly half of all workers in the American Time Use Survey are noted to have a bachelor's degree or higher—that is substantially higher than estimates from the American Community Survey.

2 U.S. Department of Labor Office of Unemployment Insurance. Report to the President and to the Congress: Implementation of the Short-Time Compensation (STC) Program Provisions in the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012 (PL 112-96). February 22, 2016.